Episode 2: It Was All A Lie

This episode explores how men of the Vietnam generation were primed for war based on the experiences of their fathers and uncles in World War II, and how that patriotism turned to disillusionment when soldiers were confronted with the realities of Vietnam.

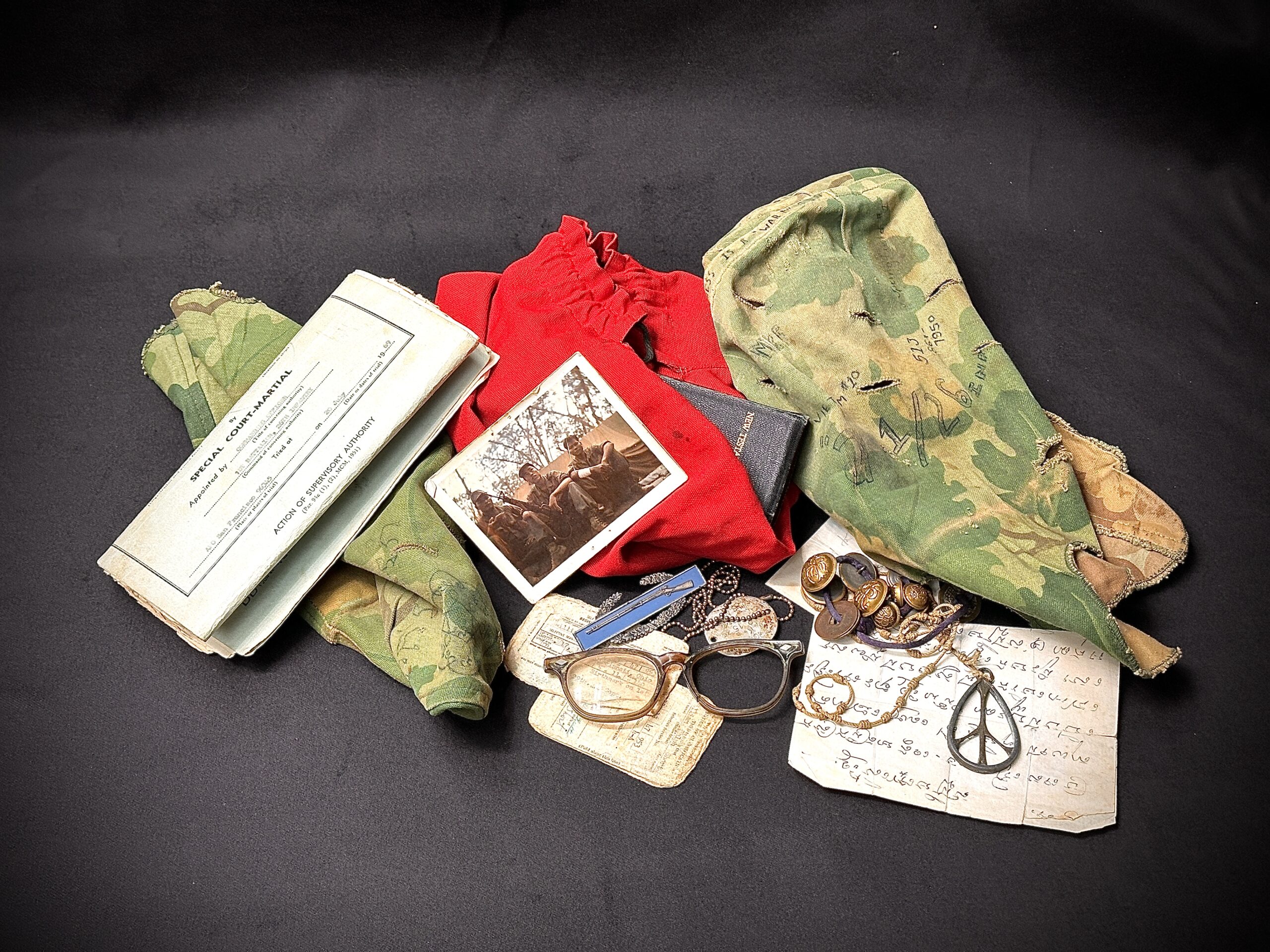

Hosts Bill Short and Willa Seidenberg take listeners on a tour through Bill’s red bag of personal war mementos, and introduces us to Marine veterans Paul Atwood and Steve Spund. They were two working class kids who acted on instinct during the brutality of basic training, and in the absence of any knowledge of the growing GI anti-war movement.

Their stories reflect conflicting feelings about their fathers, the physical and psychological trauma faced by military recruits, and the message passed down to the next generation.

NOTE: This episode contains profanity and descriptions of violence.

Guests:

● Christian Appy: Professor of History at the University of Massachusetts and the

director of the Ellsberg Initiative for Peace and Democracy

● Paul Atwood: Enlisted in Marine Corps 1965-67. Infantry, participated in the 1965 invasion of Dominican Republic. Refused to go to Vietnam. Imprisoned and discharged early.

● Steve Spund: Enlisted in Marine Corps 1965-66. Refused to go to VN, AWOL twice. Put in brig, suffered physical abuse by guards. Transferred to psychiatric ward of hospital after threatening to commit suicide. General Discharge under Honorable Conditions.

Background reading:

● Smedley Butler

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Smedley_Butler

● Vets for Peace

https://www.veteransforpeace.org/who-we-are

● Atwood’s recommended readings

Born on the Fourth of July by Ron Kovic

If I Die in a Combat Zone by Tim O-Brien

Dispatches by Michael Herr

● William Joiner Center for the Study of War and Social Consequences

https://www.umb.edu/joinerinstitute

Songs:

Country Joe and the Fish — I Feel Like I’m Fixin’ to Die Rag — 1967

The Midnight Suns – Draft Time Blues – 1966

Danny Seidenberg – For What It’s Worth – 2025

Drafted – Wilbert Harrison – 1961

The Marine Hymn – 1929

The Animals – We Gotta Get Outta This Place – 1966

Listen to A Matter of Conscience:

Follow A Matter of Conscience:

Website: https://amatterofconscience.com/

Credits:

Producers and Hosts: Willa Seidenberg and Bill Short

Producer and Sound Designer: Polina Cherezova

Associate Producer: Dylan Purvis

Assistant Producers: Ruben Flores and Aubrey Jones

Music Composer: Danny Seidenberg

https://amatterofconscience.com/wp-content/uploads/2025/05/AMOC-glossary-Google-Docs.pdf

Transcript

Transcript for Episode 2

Bill Short 00:04

Hello and welcome to A Matter of Conscience: GI Resistance During the Vietnam War. I’m Bill Short.

Willa Seidenberg 00:17

And I’m Willa Seidenberg. In this episode, you’ll hear how patriotism turned to disillusionment for Vietnam-era soldiers. And a warning: this episode contains profanity and descriptions of violence.

Music: Fixin’ to Die Rag 00:44

Willa Seidenberg 01:09

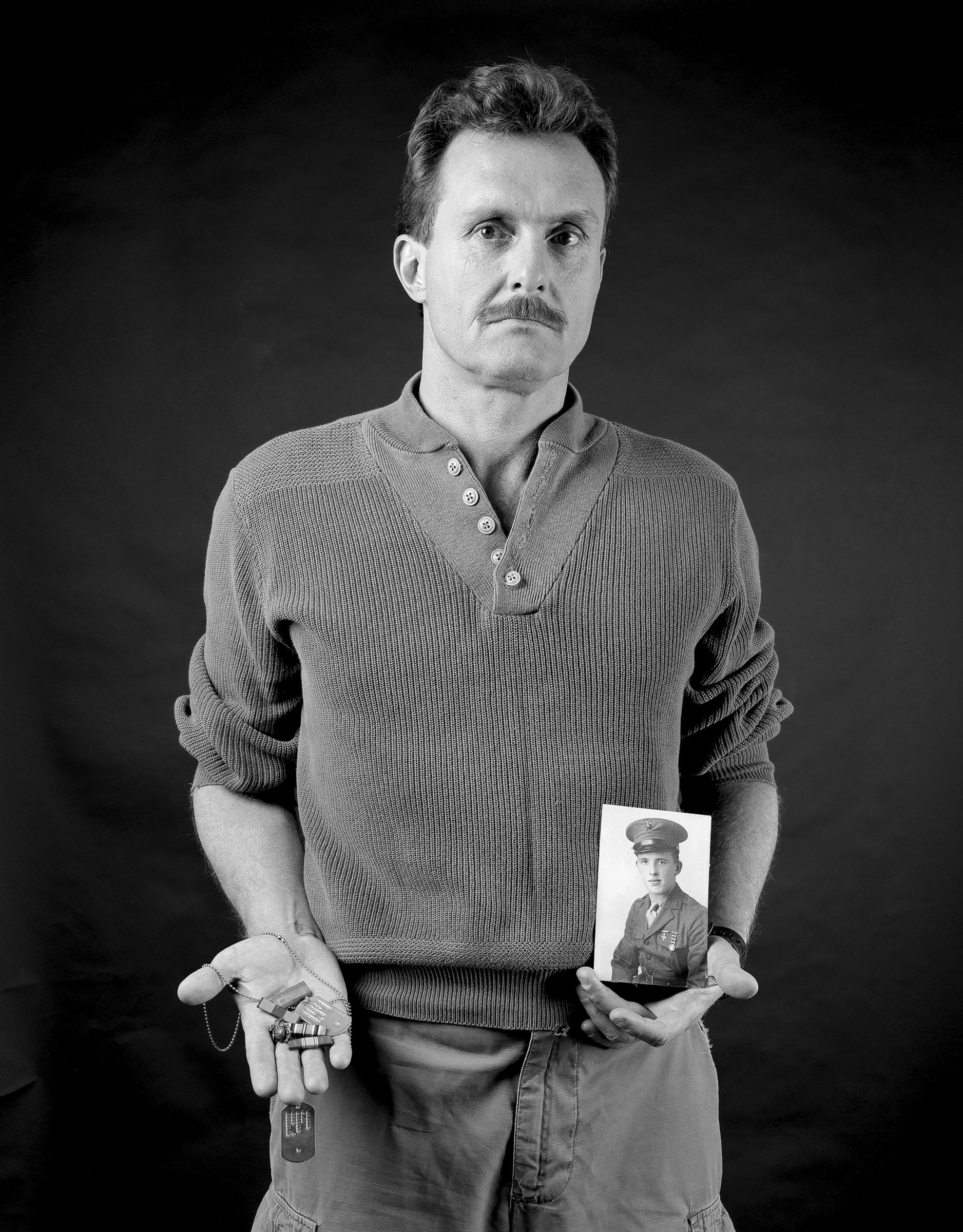

We’re going to start by looking at some mementos, the ones Bill keeps in the little red bag he’s carried with him since Vietnam.

Bill Short 01:20

So, I’ve had this bag for over 50 years, and it’s a Red Cross bag that was given to us soldiers in Vietnam. It was filled with various items like soaps and shaving gear, kind of a Red Cross personal hygiene bag. So, I’m not sure what happened to my original bag. I probably just used the stuff and didn’t think much of the bag and just threw it away. But a friend of mine in my company, Chau ____, who was a Cambodian scout in our company. He actually carried this bag in the middle of his back, even when we were in combat, because it held all of his Buddhist religious icons in it, and he felt like this red bag with his religious icons in it would protect him when we were out in the field.

02:26

He also gave me his helmet camouflage cover, on which he had written all these Buddhist icons and prayers all over it. And took the letter that he wrote that was an introduction to Buddha and also the camouflage cover, and put it in the bag and then gave it to me. And I’ve kept this bag since Vietnam, and it’s a bag that I keep all of my personal Vietnam memorabilia and a lot of family material in it as well. These are the glasses I wore. There’s still a little bit of camouflage wax on the glasses, because I camouflaged the edge of my glasses so they wouldn’t reflect when I was in the field.

03:12

This is the thing that I was really looking for. This is the peace symbol and a rosary. I left my dog tags in Oakland at a church before I went to the distribution station, and the rosary was the closest thing I could find to beads, and so I wore this teardrop peace symbol in place of my dog tags. I think in here somewhere are my father’s dog tags. Ah, I don’t have my dog tags, but I’ve got my dad’s dog tags. WK Short, U.S. Navy. This is a commemorative medal that my great great grandfather had for a veteran’s organization that he belonged to after the Civil War. It kind of reminds me of the box that my dad kept in the lower right-hand side of his bedroom dresser that had his Purple Heart in. He was wounded in the Pacific, on the destroyer he was on, it was Kamikazed, and he had a head wound, and spent some hours floating around in the Pacific waiting to be picked up after they evacuated the ship. And as a kid, I remember sneaking into his bedroom because he didn’t show it to me. He didn’t talk about his experience. It was all a mystery to me, so that made me want to see that purple heart even more. So when he wasn’t around, I would sneak into his bedroom, pull open the drawer, pull that purple heart out, and look at it and wonder if I was ever going to get one. I just thought it was the most amazing thing that I’d ever seen, that was so special that my dad would keep it private, that only he was allowed to handle and look at it. It kind of set up me accepting that I was someday going to be a soldier, and I was going to end up fighting, and maybe I would be honored by getting a Purple Heart too. That’s why this is significant, because what he collected and kept in his box, I now collect and keeping this red bag. The difference is that I’ve actually shown this to my son, Sam, and it’s something that I don’t want to keep from him. I want him to be knowledgeable and understand, you know, what the war experience was actually like.

Willa Seidenberg 05:34

So, when you look through this red bag, what do you think about? What does it make you feel like?

Bill Short 05:40

Well, it brings back all kinds of memories of, I mean, holding this draft card, I think about that first day that I was at the Selective Service Office. And one of the things that you have to do, you have to take an oath. The oath is to Oath of Service. And when you take the oath, you’re supposed to take a step forward. And that step forward is supposed to signify that you’re stepping into a new life of service to country, support and defend the Constitution the United States. And I was somewhat opposed to the war. I didn’t really understand it that much, but I was somewhat opposed to the war at that time anyway. So the only thing I could think of to do is, when we took the oath, everybody in the room of about 150 guys, took a step forward, and I didn’t I stood in one place. And I think that was the first thing that I did in the service. That was my first protest, was not taking that step forward. So I think that step forward said to me deep inside that I hadn’t really joined, I hadn’t really accepted my role, that I was still questioning my role. And at some point, you know, maybe that would manifest into something bigger than that.

Music: Draft Time Blues by The Midnight Sons 07:04

Bill Short 07:35

War memorabilia, like the ones I keep in my red bag are not only personal, they’re highly collectible. You often see them in flea markets, antique stores and auctions. I coveted my dad’s World War II mementos, and that was also true for the very first person we interviewed for A Matter of Conscience, Paul Atwood.

Paul Atwood 07:55

One of my earliest memories about my father is that he was a war hero. He spent four years in the Marine Corps, most of it overseas. I remember it came as a surprise to me to learn that my father was one of the people that I saw in the movies. He kept all his medals and ribbons, his globes and anchors from his uniforms in a little cigar box at the back of his dresser drawer, and I and my brothers used to visit it as though it were a religious shrine. Once we had been indoctrinated to believe that real men wore uniforms and went to war and performed heroic exploits like John Garfield, John Wayne,

Movie Clip from Sands of Iwo Jima 08:45

Paul Atwood 08:51

Then, you know, we wanted to see those emblems of, I mean, I used to worship them. I mean, that’s, there’s no other word for, you know, I treated them as sacred objects.

Willa Seidenberg 09:03

Kids growing up in the 1950s were inundated with messages about the righteousness of America, what historian Chris Appy calls “American Exceptionalism.”

Chris Appy 09:15

American Exceptionalism is the faith basically that the United States is the greatest country on earth, that it is exceptional in its values, its institutions, its way of life, that it is an invincible and indispensable force for good in the world. That we’re always on the side of freedom, democracy, human rights and justice. It reached its high-water mark, I believe, in the 10 or 15 years after World War II, where we emerged as clearly the greatest superpower in the world and had a kind of national sense of not just power, but sort of self-righteousness about our virtues and our role as a world leader. So, there was great confidence in that 50s and early 60s faith, along with the kind of universal idealism that the world wanted at our intervention around the world.

Bill Short 10:35

In 1985 we moved to Boston, where I got involved in a veteran anti-war group. It was called the Smedley Butler Brigade, the Boston chapter of Vets for Peace. General Smedley Butler was the most decorated Marine in U.S. history, but after 33 years of service, he resigned from the Marine Corps in protest of U.S. foreign policy in Central America and the Caribbean.

Smedley Butler 11:00

Makes me so damn mad, a whole lot of people speak of you as tramps. By God, they didn’t speak of your tramps in 1917, and ‘18.

Bill Short 11:07

He called himself a high-class muscle man for big business, Wall Street and the bankers. My favorite quote from him was when he referred to himself as a gangster for capitalism.

Willa Seidenberg 11:20

Smedley Butler was also a strong advocate for veterans. After World War I, Congress promised to give the veterans a bonus, but the catch was they wouldn’t receive the money until their birthday in 1945. That was more than a decade later, but the veterans needed it sooner. Remember, these were the Depression years, and people were really hurting. In 1932, 43,000 veterans camped out all over the nation’s capital demanding those bonuses, and Smedley Butler was their passionate champion.

Smedley Butler 12:00

Let me tell you something. I’ve been all over the world. I’ve seen you fellas on the streets in Washington, there isn’t this well-behaved group of citizens in the world.

Bill Short 12:10

Smedley Butler was the perfect symbol for the anti-war vets in Boston in the 1980s. We were activists against the Reagan Administration’s intervention into Central America where Butler had once served. It was through my work with the Butler Brigade that I met Paul Atwood and started this project. After not seeing Paul for some 30 years, we reconnected last year. I just want to thank you for activating this whole part of my life of re-examining the war, because when I became involved with the Butler Brigade, and this is like 1986. I had never really talked much about my history or about my background to that point, you’re the first person I opened up to and actually told about my history and with the war.

Paul Atwood 12:58

I’m glad that I was able to talk to you, you know, because it opened it up for me too. But I still don’t talk to too many people about it. You know, only veterans or other people who have a sense of what the Vietnam War was about and what American foreign policy is really about and always has been.

News Report 13:33

Meanwhile, the U.S. Marines have also taken center stage in South Vietnam.

Willa Seidenberg 13:37

In March of 1965, Army combat troops, plus a Marine brigade, landed in Da Nang, that’s along the coast of central Vietnam. It was the first major deployment of U.S. ground forces in Vietnam. And just a few months later, President Lyndon Johnson announced the U.S. was sending even more troops.

President Lyndon Johnson 14:00

I have today ordered to Vietnam the Air Mobile Division and certain other forces which will raise our fighting strength from 75,000 to 125,000 men, almost immediately. Additional forces will be needed later, and they will be sent as requested.

Willa Seidenberg 14:20

Close to three million soldiers would eventually serve in the Vietnam War, and millions of others served in bases elsewhere around the world. Most Americans couldn’t even find Vietnam on a map in 1965 but suddenly, young American men were facing a big choice, either enlist in the military or be drafted, unless you were in college and then you could get a deferment.?

Bill Short 15:19

Paul says he didn’t see himself as an anti-war activist, but his story is emblematic of why so many of us turned against the military and the war in Vietnam. Paul and I, and many veterans revered our father’s service in World War II, but we also had to deal with our fathers’ post-war trauma.

Paul Atwood 15:39

Ten years later, was having nightmares that rocked the house that nobody could understand. I had no idea to connect them with the war, not until much later.

Bill Short 15:50

Paul’s father was an alcoholic, like many World War II veterans. Paul’s home life was filled with turmoil, and things weren’t much better outside the home. He was a street kid in a tough neighborhood in the Roxbury section of Boston.

Paul Atwood 16:05

As a result of my father’s alcoholism and the breakdown of the family, I became a juvenile delinquent. That’s the term they used to use in those days.

Willa Seidenberg 16:14

Paul was drinking by the age of 13, and he was getting into all sorts of trouble.

Paul Atwood 16:20

I was a primitive revolutionary, angry at a lot of things, not really understanding any of them, but acting out. So, I would, you know, steal a car and deliberately crack it up.

Willa Seidenberg 16:33

Finally, he went too far and almost ran over a metropolitan cop.

Paul Atwood 16:38

Wake up a bloody pulp in the cell the next day and get hauled before a judge. Only this time the judge said, “Well, I’ve had enough of you. You have a choice. You can go in the military, or you can go to prison. Take your pick.”

Willa Seidenberg 16:53

That was a really easy choice for Paul. Since his father had been a marine during World War II, Paul always assumed that he, too would serve in the military. He was like so many kids in the 1950s and 60s, looking for meaning in their lives.

Chris Appy 17:15

I think one of the reasons that President Kennedy touched so many Americans, including a lot of young Americans, is his invitation to try to serve America around the world.

President John F. Kennedy 17:27

And so my fellow Americans ask not what your country can do for you. Ask what you can do for your country.

Bill Short 17:38

Paul was only 17 when he signed up for the Marine Corps, he was sent to Parris Island in South Carolina, where he was immediately confronted with the brutality of basic training.

Paul Atwood 17:49

I have to say that I was absolutely terrified from the first day on. I mean, terrified, but I was also resolved that under no circumstances would I break because that would have been just too dishonorable.

Bill Short 18:02

Paul survived 13 weeks of basic training at Parris Island, including a practical joke his father played on him.

Paul Atwood 18:09

Every time you got a package from home; you were required to open it in front of the rest of the platoon. So I get a package from him in the mail. Of course, he knows that I’m going to be required to open it right in front of the entire platoon, so I do. And what is it? It’s a volume of poetry by Elizabeth Barrett Browning.

Bill Short 18:34

Not only did Paul have no idea who Elizabeth Barrett Browning was, but he had never even read a poem.

Paul Atwood 18:41

Well, the drill instructor looked at this, and he says, Elizabeth Barrett Browning. And it was Sonnets from the Portuguese, right? And he started screaming, “what the fuck kind of fairy ass fucking bullshit is this?” He went in, he got ribbons. He made me wear ribbons on my ears. He made me kneel in the middle of the squad bay and recite the fucking poems, and I was so fucking mortified that I was beside myself. How could my father do this to me in the middle of the very center of the cult of masculinity? He knew exactly what kind of response this was going to draw. I think he just went in looking for a book of poems that would look so utterly fairyish.

Willa Seidenberg 19:57

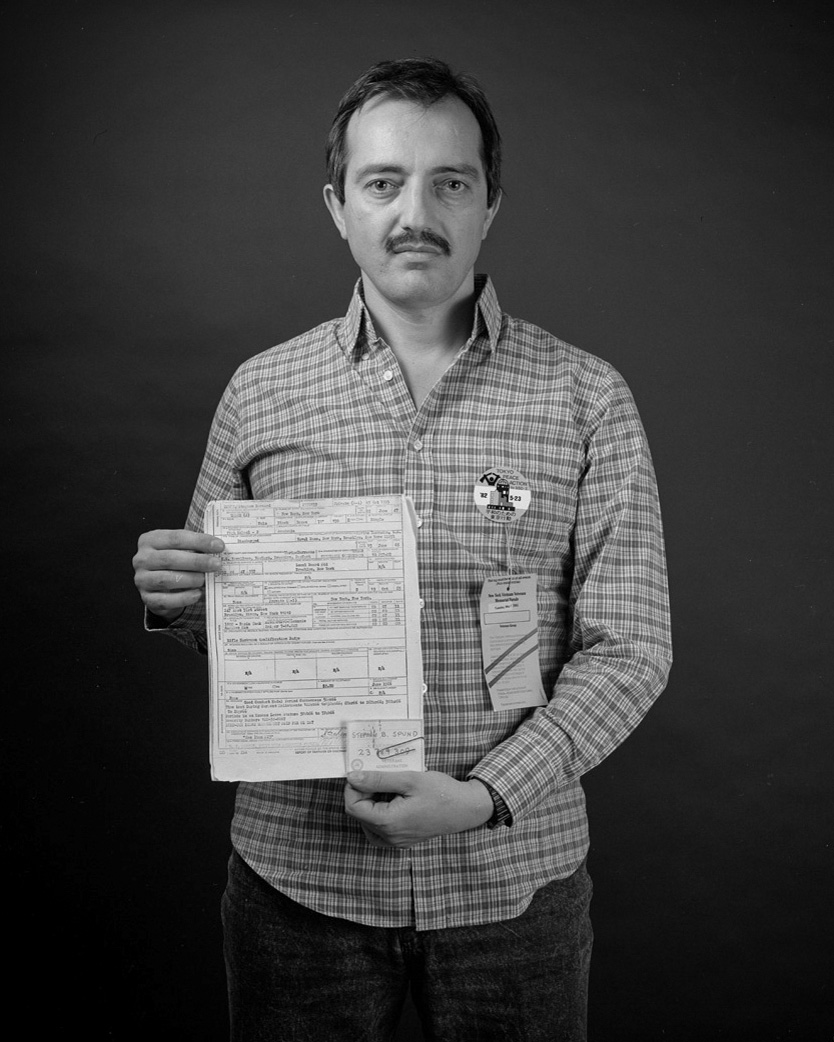

Paul Atwood’s story is really similar. To another Marine veteran. We interviewed Steve Spund. Steve’s father didn’t serve in the American military. He was a Polish Jewish immigrant who was proud to be an American. Steve also grew up in a tough neighborhood in Brooklyn, New York, and he was a high school dropout.

Steve Spund 20:20

In my father’s eyes and also my family’s eyes, possibly even in my own eyes, I was a failure, never having completed anything really that that I started out to do, probably one of the strong reasons why I enlisted in the Marine Corps not only to be different, but more so to be the best.

Willa Seidenberg 20:43

Steve’s father was thrilled when he enlisted, but it all turned sour when Steve went through basic training. He and other recruits were hearing disturbing stories from Marines coming back from their service in Vietnam.

Steve Spund 20:58

Totally contradicted everything that I believed in about the U.S., and I’d grown up seeing the U.S. defend itself against the Nazis and Japanese and John Wayne movies and felt very patriotic. Maybe I’d seen one or two too many marine movies, but I felt it myself, and it was supported by my father’s patriotism went along very well that what we were doing had to be right.

Willa Seidenberg 21:28

But the returning Marines that Steve met were saying that what America was doing in Vietnam was wrong and that he shouldn’t go.

Steve Spund 21:37

I refused for the first month or so to believe that even though there was more than one person, I felt that these people had to be troublemakers or malcontents or something like that, to be talking so negatively about the Marine Corps and about Vietnam.

Willa Seidenberg 21:57

This was all incredibly confusing to Steve, and when he called home to talk to his family, his father.

Steve Spund 22:04

Turned the deaf ear to me.

Bill Short 22:10

By this time, Steve was pretty mixed up. He tried to tell his company commander and then the base commander that he was having misgivings about the war, they just sent him away. So, he tried the base chaplain.

Steve Spund 22:21

He was worse than the captain. He had his pistols hanging on his coat rack. He had his .45 slung over there. And I said, “Oh God.” He said, “It’s your duty to serve, and if you have to be killed, you know to do your duty.” I said, “Aye, aye sir.” I turned around, and I knew that whatever I did, I’d get no support from anyone on the base.

Bill Short 22:44

I had a similar experience with my company chaplain in Vietnam. I was ordered to see the chaplain to talk about my opposition to the war. Apparently, the military thought a U.S. Army chaplain was going to straighten me out when I walked into his hootch. He was busy cleaning his personal collection of captured enemy weapons, which included a Chinese nine-millimeter pistol. His first comment to me was, “Your unit has seen quite a bit of action recently. So why don’t I get you a three-day pass to Vung Tau to think things over.” I thought, Vung Tau. Vung Tau was a beach resort used by in-country GIs to find prostitutes and do drugs. I was shocked that this man of the clergy would offer me a visit to Vietnam’s Sin City.

Willa Seidenberg 23:35

The military’s response to Steve was to work him harder and just tire him out. They gave him extra duty that was physically demanding.

Steve Spund 23:45

So, the only thing that I could think of was to get some space, and that was to go AWOL. So that’s what I did. I figured the only place that I could go where I knew that people that I could trust would be back in New York, back at home.

Willa Seidenberg 23:58

But even at home, trust was hard to come by. They sent Steve to the Marine barracks at the Brooklyn Navy Yard, and just to get the military off his back, he agreed to return to his base in North Carolina. And it was pretty remarkable that they gave him a bus ticket and just sent him on his way.

Steve Spund 24:01

I told my family that I was on a 30-day leave. But after the 30 days were up, my father was very suspicious that I didn’t have leave papers. A short time after the 30-day period, I was awakened by the police in my own house, and my father called the police and reported me? So, I didn’t go back. I went back home, back to your parents, back to my parents’ house.

Bill Short 24:46

Steve doesn’t remember what he told his father, but it wasn’t too much later that his father turned him in again.

Steve Spund 24:53

This time the police didn’t come, though I think they must have called the MPs, and they came and they woke me up. This time, they didn’t bother with the Marine barracks. They took me over to Third District Naval Brig in Brooklyn, Navy Yard, and I started to get worked over by the marine guards.

Bill Short 25:15

When Steve told us this story, we had a hard time understanding how his father could send him back, but Steve was forgiving.

Steve Spund 25:24

I knew my father was capable of doing what had to be done, but I was hurt. Of course, I’m sure he didn’t do anything to hurt me intentionally, even then, but I was surprised that he didn’t try in another way to find another answer or another way, but now, in hindsight, he probably just didn’t know what to do.

Willa Seidenberg 25:57

Paul Atwood was also experiencing physical and psychological abuse during his basic training. Often the drill sergeant would beat the trainees. It was a way of intimidating and controlling them. The first time it happened to Paul, it was because he wasn’t wearing a belt.

Paul Atwood 26:16

Like a cobra. He snapped that belt out and wrapped it around my throat and pulled on it until I passed out on the deck, unconscious. I mean, I was only out for maybe 10 seconds at the most, right? Just enough to put me out, right? But I remember the feeling of my eyes going, Whoa, as the pressure built, you know? And then looking at him, I remember looking into his fucking eyes, and they were like, you know, he was fucking getting pleasure out of watching me fucking go unconscious.

Willa Seidenberg 26:47

Paul survived his basic training, and then he was sent to Camp Lejeune in North Carolina for infantry training. At one point, his unit was ordered to Santo Domingo. The United States had invaded the Dominican Republic the previous spring. They were trying to put down a rebellion against the Dominican government.

News Report 27:11

President Johnson ordered Marines into the country to protect the democracy.

Paul Atwood 27:16

On landing ship, I remember saying out loud, I wonder what side we’re on? You know, like, hahaha. The first sergeant started screaming, what fucking boot camp did you go to, you fucking asshole? What side are we on? Doesn’t matter what side we’re on. You’re a United States Marine, you know, you kill who we tell you to kill, period,

President Lyndon Johnson 27:37

The American nation cannot, must not, and will not permit the establishment of another communist government in the Western Hemisphere.

Willa Seidenberg 27:56

For Paul and his unit, the invasion was a big yawn.

Paul Atwood 27:59

I didn’t do anything. All I did was fill sandbags the whole fucking time was there, ride up and down the beach in an Amtrak.

Bill Short 28:05

The real turning point for Paul was when he was sent back to Camp Lejeune, a huge base of 50,000 Marines. The trainees spent weeks in the woods playing war games.

Paul Atwood 28:16

On this particular day, we had been firing at a target about a mile away, but we had finished firing. We were just sitting there, and the next thing you know, we got hit with artillery fire, right? Just like all of a sudden, shells started coming on us. You know, the NCOs are screaming for everybody to start cutting. We were all clustered, right? He says, get the fuck out, you know. And you know, I remember going down on the ground and just pushing my fucking face into the fucking ground, pulling my helmet over me, and just like this on the ground, saying, what the fuck is this, you know. And then it was over, you know, just like, just as quickly as it began and it was over, and I get up and I’m fucking blown away, right? I just am not the same person anymore.

Bill Short 29:16

Three people died in that training exercise, and it was the first time Paul really understood that being in the military wasn’t just playing war games. He could die.

Paul Atwood 29:33

That was the most frightened I’ve ever been in my life. I can remember the smell of my own fear. It was as though the adrenaline pumping through my veins lit the membranes of my nose on fire.

Bill Short 29:47

Everyone in the unit was dazed by the shelling, yet no one talked about it.

Paul Atwood 29:51

It was like a conspiracy of silence. After that, you know,

Willa Seidenberg 29:55

Paul started questioning everything he and his fellow Marines were doing. His moral and religious beliefs were clashing with what he was seeing in the military.

Paul Atwood 30:06

No matter what you do, it’s going to be interpreted that you’re a fucking coward or a traitor or malingerer or whatever. I mean, I started feeling the same way I felt as a teenager. You know, fuck you all. Another fucking set of lies, another great, big hypocrisy. And so one day, in a fierce argument with a sergeant in the barracks, I finally blurted out, I said, you know, the fucking peaceniks are right. We’re fucking baby killers or some such shit. I don’t know exactly what I said. I said it in real anger, though, could have heard a fucking pin drop after that, like everybody stopped and just stared.

Willa Seidenberg 30:44

Paul’s Christmas leave was canceled, so he had to stay on base for the holidays, and one night, as he was going back to his bunk, he was jumped by five guys in ski masks.

Paul Atwood 30:57

And they didn’t rob me. They just beat me to a fucking pulp, so I spent Christmas day in the base hospital with cracked ribs and a concussion and seriously, seriously beat up.

Willa Seidenberg 31:08

Paul suspected his attackers were from his unit. He recovered from the beating and was sent home on leave in January. He became increasingly depressed, turning to drugs and alcohol, and then came another violent run in with police. That’s when Paul ended up in a straitjacket with his father, calling him a traitor.

Paul Atwood 31:32

I wound up in a psychiatric unit, but for the first two days, maybe even three, I was in a straitjacket and a padded cell and drugged. But one day, one morning, my father appeared standing over me, and he said, “You are a one pathetic piece of shit. You are, you know, you’ve harmed the family name it still gives me the willies.”

Willa Seidenberg 32:01

Paul was in lockup for 30 days, and then he was sent to the Boston Navy Yard. Everyone in the barracks stayed far away from him. He was kind of like a leper, and finally, he just walked away from his post. That led to yet another violent run-in with a Boston cop, and before long, the shore patrol picked him up.

Paul Atwood 32:26

And they pulled me before the Sergeant of the Guard. And the Sergeant demands my military ID. So, I reach in my pocket and I pull it out, and just as I give it to him, I decide I’m going to punch him too. So, I do. I punch the Sergeant of the Guard. This is another serious charge, right? And then I wake up a bloody fucking pulp the next day in the jail cell because I’ve just invited all kinds of abuse on myself.

Bill Short 32:53

Paul spent eight weeks in solitary confinement. He was facing at least two years in a naval penitentiary, but unbeknownst to him, his mother and grandfather had appealed to their congressman, former Speaker of the House, John McCormack. He managed to get Paul an honorable discharge without a court-martial. But Paul says his circumstances were less than honorable.

Paul Atwood 33:17

Not honorable to my family, not honorable to myself, not honorable to any of the people I was serving with. It wasn’t like I was taking a principled moral stance, because I didn’t even know how to do that. Then all I knew was that something was seriously wrong, both within me and without me, and I didn’t know what to do about it, and I behaved in an irrational manner that got me into a lot of trouble and eventually got me kicked out of the Marine Corps. While it had become clear to me that I didn’t want to go to Vietnam, I also didn’t want to be, you know, dishonorably discharged from the Marine Corps.

Bill Short 33:53

Paul rented a room in Boston and mostly kept to himself doing drugs and not telling anyone he had been in the military, that is until about a year later, when he went to an anti-war rally and met some vets from VVAW, Vietnam Veterans Against the War.

Paul Atwood 34:09

And then I began to start to make some serious intellectual analysis, of what was going on, not only with the war, but with everything else.

Bill Short 34:19

He started reading Karl Marx and other radical thinkers, that helped him make some sense of the confusion and chaos he had personally experienced. He didn’t speak to his father for five years, and then it was another five years before they actually did more than just say hello to each other.

Paul Atwood 34:37

I once wrote him a long, long, long letter about all this stuff. As a matter of fact, it was at Christmas, I gave him four what I considered then the best books about Vietnam. Ron Kovik’s, Born on the Fourth of July, Tim O’Brien’s, If I Die in a Combat Zone, Michael Herr’s Dispatches, and I can’t remember the fourth one right now, but I boxed them up and put the letter in with those. I know he read it, but he never so much as acknowledged that he ever got it or read it or anything.

Willa Seidenberg 35:10

Paul got it together enough to attend the University of Massachusetts in Boston, where he studied history and political science. He taught at an alternative high school, then went to graduate school. He eventually helped establish the William Joiner Center for the Study of War and Social Consequences at UMass, Boston. Today, Paul is teaching history at UMass, and his courses take a critical look at U.S. foreign policy,

Paul Atwood 35:42

And I began to realize that these younger students today know the world is fucked up. Many of them in particular, are concerned about climate change. You know, they don’t think about the threat of atomic nuclear war, but you know, that’s part of it, and then climate change is only going to accelerate the dangers of war. So you know, I’m able to reach them.

Bill Short 36:29

Steve Spund contemplated suicide and ended up in a psychiatric ward at the naval hospital. After 10 weeks, he was discharged from the Marines.

Steve Spund 36:39

I received a general discharge with honorable conditions at the Brooklyn Navy Yard. I had to go there to receive my separation papers. I thought it was very strange, not only to be there, but the Second Lieutenant Marine. Soon as he handed me my papers, he asked me, and he was serious, he asked me if I would like to enlist again. And I don’t remember the vulgarity I used, but I’m sure I let him know that I wasn’t interested.

Bill Short 37:14

Well, I guess that Marine lieutenant was kind of clueless. When Steve came out of the service, he had no training and couldn’t get a job. And for a while, he had survivor’s guilt, until he ran into some veterans at an anti-war demonstration in Washington, DC.

Steve Spund 37:30

Dewey Canyon II, they called it. And all of the veterans there told me that I did the right thing. I didn’t want to talk about my experience because I I didn’t serve, and they did, and I didn’t go and they did, and I felt not so much a coward — I woulda put it on the line for the right reason, but I didn’t want to go there after what I heard. Surprisingly, they all convinced me that I did the right thing, that I did the harder thing than they did. And at first I didn’t believe that. When we got to the point where we did a march of Pennsylvania Avenue, they insisted that I go into the front row with the combat Marines and march with them.

Bill Short 38:20

Steve had turned to drugs when he got out of the military and only started to turn his life around after a couple of friends died from heroin overdoses in the early 1970s. He went back to school and eventually started working in data processing.

Willa Seidenberg 38:51

As we were going through Bill’s red bag of memorabilia, our son Sam came in. He’s 26 and the specter of Vietnam has always been present in his life.

Sam Short 39:03

I feel like the last time dad and I talked about this stuff, it was like a late-night emotional conversation. We both been drinking together or something like that. But I remember most of it.

Willa Seidenberg 39:14

So I’m curious, Sam, you know that the men in his family were in war, and that stops with you.

Sam Short 39:25

Yeah, well, I think it stopped with him first. I mean, I would never have been in the military because of him.

Willa Seidenberg 39:31

And why is that?

Sam Short 39:32

Because I think he said one time, if there was ever a draft, he was going to ship me to Canada or something like that. I guess there was always sort of a mystique about it. Guns weren’t allowed to be in the house, or not even Nerf guns or anything. So maybe I had, like, an interest out of that, but I don’t think I would have ever been like, oh, I want to go join the military or something like that.

Willa Seidenberg 39:54

I got the feeling that even though you were sometimes disappointed that Dad didn’t want you to have toy guns, that you kind of understood where he was coming from, or you at least respected it.

Sam Short 40:07

Oh yeah, as a kid, yeah, definitely. I think was hard when, like, all my friends were playing, like, Call of Duty, and I couldn’t play with them. I think I always understood it, at least. Even when I was a little kid at a certain level, like, of why he didn’t want it. I guess I never really even understood the significance of a gun until I shot one for the first time, when I was in Montana, and I shot, like, actually, well, .22 and like, the power I felt from shooting it, it was like a scary thing. And so I think that gave me more perspective, too, as to why he would never want even something resembling a gun in the house. If you can see firsthand, like the damage that it can do, the bang and the impact is like it’s terrifying, terrifying sound.

Bill Short 40:55

I’m grateful my son never had to face the horrors of war. Most soldiers in Vietnam were only 18 or 19 years old, and the brutal and inhumane training in the military caused many young recruits to question the fairness of their treatment. Like Paul Atwood and Steve Spund, that opened them up to questioning the military at large, and especially our involvement in Vietnam. The next step for many was direct action against the war.

Willa Seidenberg 41:35

Next time on A Matter of Conscience:

Chris Appy 41:39

The American withdrawal in 1973 was an acknowledgement that there was nothing we could do to really make this history different.

Willa Seidenberg 41:48

If you don’t know much about the history of the Vietnam War, this next episode will be helpful for understanding the context for GI opposition to the war.

Bill Short 42:00

This podcast is independently produced with crowdsourced funds. We thank the dozens of people who donated, and you can join them by going to our website amatterofconscience.com. You can also see a glossary of terms and show notes for this episode.

Willa Seidenberg 42:16

This episode was produced by Willa Seidenberg, Bill Short and Polina Cherezova. Dylan Purvis is our associate producer, and the assistant producers are Ruben Flores and Aubrey Jones. Many thanks to Country Joe McDonald for giving us permission to use his song as our theme music. All the original music in the podcast is by Danny Seidenberg. The Star Spangled Banner was performed by Andrew Patinkin. Sound design is by Polina Cherezova. Web design by Christian Knudsen. We thank the Kazan McLain Partners Foundation for their generous support. Our fiscal sponsor is the International Documentary Association. Thanks also to Denise Abrams, Bill Belmont, Sam Short, Susan Schnall and Veterans for Peace, and David Zeiger. And finally, our heartfelt thanks go out to all the veterans who shared their stories with us.