Episode 1: The War Against the War

In this first episode of A Matter of Conscience, you’ll hear about an important part of the war in Vietnam that history books don’t talk about — the GI anti-war movement. Bill Short, a photographer and once-Vietnam soldier, and Willa Seidenberg, a journalist and professor, set the scene for the emergence of the GI anti-war movement and showcase acts of defiance. Along the way, we hear the personal accounts from veterans who faced internal conflicts between their duty and their conscience.

Note: This episode contains profanity and descriptions of war and violence.

Show Notes

Guests:

- Christian Appy, a Professor of History at the University of Massachusetts and the director of the Ellsberg Initiative for Peace and Democracy

- Dennis Stout, Enlisted Army 1966-69 and served in VN with 101st Airborne

- John Tuma, Enlisted Army 1969-72 and served in VN as an interrogator

- Susan Schnall, Enlisted Naval Reserves 1965-69 and served as a Navy nurse stationed in SF

- Alan Klein, Enlisted Air Force 1966-67

Background reading and other resources:

- Operation Dewey Canyon III organized by Vietnam Veterans Against the War in April 1971

- Operation Dewey Canyon military action

- The Nuremberg Trials

- Soldiers in Revolt: The American Military Today, David Cortright. Haymarket Books; First Edition (September 1, 2005)

- Waging Peace in Vietnam: U.S. Soldiers and Veterans Who Opposed the War, edited by Ron Carver, David Cortright, and Barbara Doherty. NY: New Village Press, 2019. See website.

- “The Collapse of the Armed Forces,” by Col. Robert D. Heinl, Jr., Armed Forces Journal, 7 June 1971.

- Books by Christian Appy:

- American Reckoning: The Vietnam War and Our National Identity Viking, 2015)

- Patriots: The Vietnam War Remembered from All Sides (Viking, 2003).

- Cold War Constructions: The Political Culture of United States Imperialism, 1945-1966 (University of Massachusetts Press, 2000). Editor

- Working-Class War: American Combat Soldiers and Vietnam (University of North Carolina Press, 1993).

- Vietnam War Song Project: an incredible collection of songs about the Vietnam War

Songs:

Country Joe and the Fish — I Feel Like I’m Fixin’ to Die Rag — 1967

Creedence Clearwater Revival — Fortunate Son — 1969

Country Joe MacDonald — Kiss My Ass — 1976

Danny Seidenberg — In-A-Gadda-Da-Vida — 2025

Danny Seidenberg — I Ain’t Marching Any More — 2025

Timecodes:

(3:48) The search for the church

(13:13) Setting the scene for the anti-war movement in the military

(26:36) Staying true: conscience vs. orders

(30:11) Next time on A Matter of Conscience

Listen to A Matter of Conscience:

Follow A Matter of Conscience:

Website: https://amatterofconscience.com/

Credits:

Producers and Hosts: Willa Seidenberg and Bill Short

Associate Producer and Sound Designer: Polina Cherezova

Associate Producer: Dylan Purvis

Assistant Producers: Ruben Flores and Aubrey Jones

Music Composer: Danny Seidenberg

Transcript

William Short 00:07

Hello and welcome to A Matter of Conscience: GI Resistance During the Vietnam War.

Skip Delano 00:12

I got there in May, and by August, I was very clearly against the war.

Dave Cline 00:21

I made a decision that I was going to come back to the United States and start working against the war, because I felt that we were wasting American lives and Vietnamese lives pointlessly. And

Greg Payton 00:34

And I went to the stockade, and it was all these Black people and all these brothers man that blew my mind.

Chris Appy 00:43

By 1970, ’71 you could find more acts of open defiance and dissent on an average American military base, as you would find on any American college campus.

Dave Hockabout 00:57

We have to let people know that there are guys in the military and women in the military that don’t support what our government’s doing, and we need to get the word out.

David Cortright 01:06

And I really had this overwhelming sense of injustice and immorality of what our country stood for.

Music: Fixin’ to Die Rag 01:21

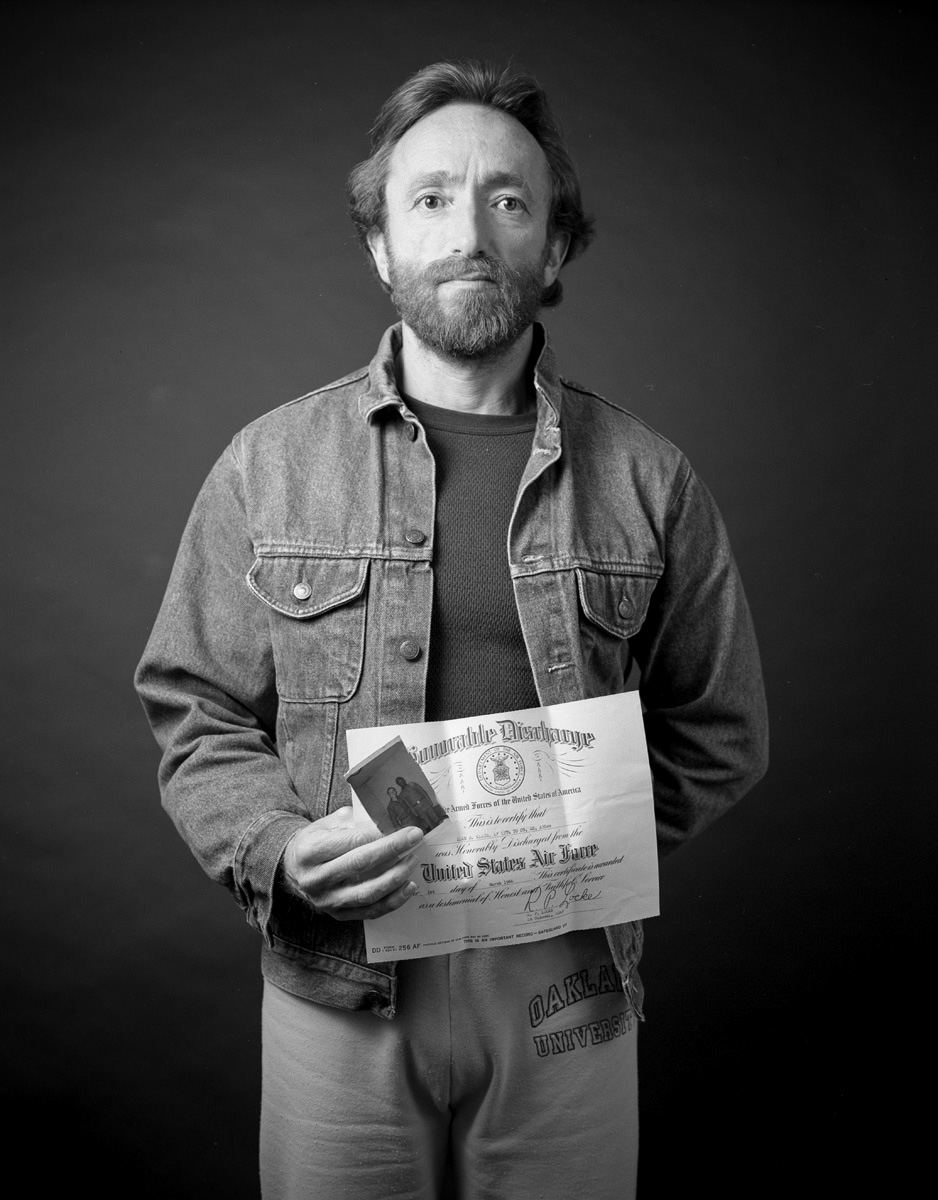

William Short 01:35

I’m Bill Short, photographer and artist. I was a soldier in Vietnam in 1969, and after four months in combat, I refused to keep fighting. I was court-martialed twice and sent to a U.S. military prison in Vietnam.

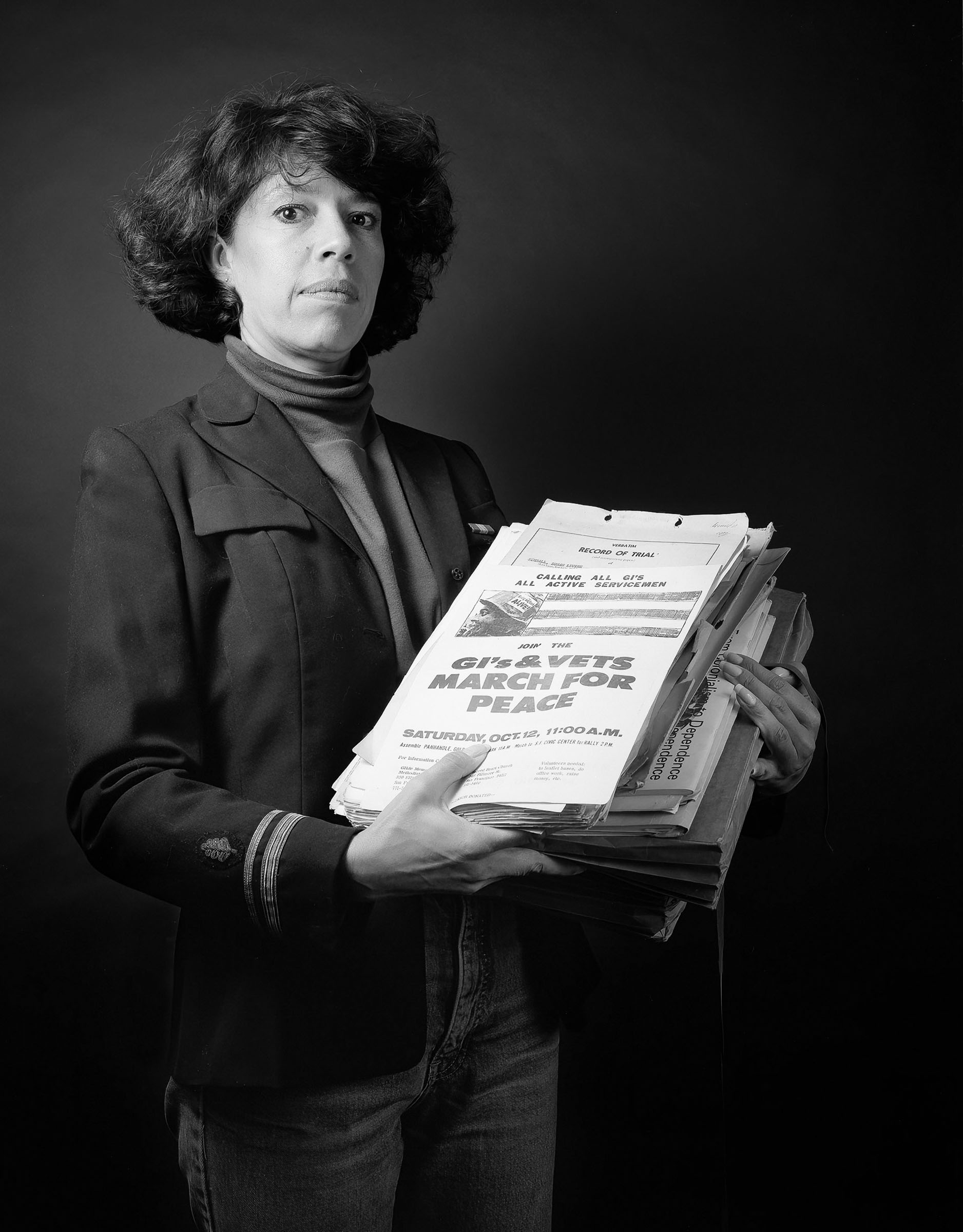

Willa Seidenberg 01:50

And I’m Willa Seidenberg, a journalist and Professor Emerita at the University of Southern California.

William Short 02:02

That’s Fixin’ to Die Rag by Country Joe and the Fish, a song I listened to over and over again when I was a soldier in Vietnam. The song spoke directly to me because of its absurdity and anti-war message. Many of you may know the song from the Woodstock album or film.

Willa Seidenberg 02:25

This is our very first episode of A Matter of Conscience. In this episode, you’ll hear about an important part of the war in Vietnam, the history books don’t talk about: the GI anti-war movement. Before we get started, we want to tell you that this episode contains profanity and disturbing descriptions of war. When Bill and I first met around 1980, Vietnam seemed like it was far in Bill’s past. But it was only ten years before, and over these past 45 years that we’ve been married, Bill’s experience as a combat soldier and a GI resister has always hovered in the background of our marriage.

William Short 03:27

Yeah, it’s always been a part of who I am. For ten years, I tried to forget I’d ever been in the military. I’m probably like a lot of veterans who have had to confront their wartime demons. Sometimes we need to face those memories head-on in order to find some peace with them. I’m doing it by using my wartime experience as inspiration for creative work. Long ago, when I was on my way to Long Binh, that’s the U.S. military stockade in Vietnam, I promised myself that someday I would make amends — amends for my participation in the war against the Vietnamese. This is my contribution to helping all Americans understand our involvement in Vietnam.

Willa Seidenberg 04:08

Along the way in the podcast, you’ll hear bits and pieces of Bill’s story. And as we thought about how to approach telling the stories of GI resisters, we’ve been diving even deeper into Bill’s memories. And that led us on a search for a church.

On-Scene Audio 04:26

Here we are on our way to Oakland to see if we can find the church that Bill visited in 1969 when he was being shipped off to Vietnam from the Oakland Army Base.

William Short 04:45

It’s been a long time. It was 1969, so I don’t know if we’re actually going to find it. Everything has changed a lot, and my memory’s a little foggy.

Willa Seidenberg 04:56

Our first stop was the First Unitarian Church of Oakland. California.

Does anybody know where the army base is? The reason we’re asking is, he shipped out to Vietnam in 1969 from Oakland Army Base.

William Short 05:21

I left my dog tags hanging in a church before I went. And I think it was this one, because I’ve seen pictures of the inside of the church online. So I remember there were three crosses, and I left my dog tags hanging on one of the crosses.

Congregant 05:36

I think you’ll be disappointed. We don’t have any crosses. I don’t think there’s ever been crosses,

Willa Seidenberg 05:40

Really? So it might not have been this church. So it was back to square one.

Can you talk a little bit about the significance of dog tags when you’re in the military?

William Short 05:54

Well, you know, if I had been killed in action, I would have been probably MIA, because you have two dog tags. They’re connected by two chains. One is a chain that goes around your neck that holds one dog tag. Then there’s a smaller chain that holds the second dog tag. The reason you wear two is, in case you get killed, they can take one, place it in your mouth, between your teeth, and then slam your chin up on it and kind of embed the dog tag in your teeth. So, if your body is ever found in the future, then that dog tag is wedged into your skull. The other dog tag your company commander would have collected from one of the sergeants that would have stripped it off your body.

Willa Seidenberg 06:38

And nobody checks to see whether you have dog tags when you know, get on the plane?

William Short 06:46

No, it’s like one of those oversights that you know nobody ever looked.

Willa Seidenberg 06:52

Do you remember being able to see the water?

William Short 06:57

No, I just remember it being a huge building that was filled with double-decker bunks. All these buildings are new.

Willa Seidenberg 07:06

When we struck out finding the church, we pulled over to the side of the road, and Bill told me more of the story. Let’s back up a minute and talk about when you got here.

William Short 07:19

Well, let’s go back even farther. I left from my parents’ house. I was in my dress uniform. I was a newly graduated sergeant from Non-Commissioned Officers Candidate School. My dad was so proud of me that he and my mom flew to Fort Benning to watch my graduation when I received my stripes.

Willa Seidenberg 07:38

Really? You never told me that.

William Short 07:39

Yeah, when I graduated from NCOC school, I went to Fort Lewis to work as an assistant drill instructor. And then I got a 30-day leave to go home. That was in, I guess this would have been in January sometime, because I shipped out, I think it was February 8, to Vietnam. But I remember my parents took me to the airport. It was one of the few times, I think, only the second time I’d ever seen my dad cry. As I was going out the door to board the plane — then you just walked out on the tarmac and climbed the stairs — I looked back and I could see him holding his hand to his eye, wiping some tears away. And you know, that was pretty emotional for me. And then I flew out here, and I don’t remember how I found this hotel I stayed in, but I remember it was a real funky hotel, like your typical fleabag hotel that you might see in a cheap flat foot detective movie. I went there because I was going to spend the night and try to figure out if I was going to go AWOL and go to Canada or if I was going to go to Vietnam.

Willa Seidenberg 08:55

So why were you considering going AWOL, and how did you even know about doing that?

William Short 09:02

Even from the very first day that I entered the military service, I was pretty much sure that I didn’t want to go to Vietnam. I didn’t think the Vietnam War was right, but I felt stuck. I felt like a lot of young men at that time that you get caught up in this whole idea of your responsibility to serve the country, and that meant serving your family.

Willa Seidenberg 09:30

And had you met anybody that had gone AWOL or deserted?

William Short 09:35

I didn’t really know anybody who purposely deserted or left the military because they were opposed to the war, but there were certainly guys in basic training who refused orders. In fact, there was a guy in my basic training unit who probably the second week of basic training, who just refused to do anything. He refused to stand up at the position of attention. And he refused to step forward when the drill sergeants would tell you to step forward. He basically just stood there like a lump, and the sergeants would yell and scream at him, and he would just kind of ignore them. You know, I talked to him somewhat. I was kind of friendly with him, and he said he just didn’t want to serve. He didn’t want to go to Vietnam. Didn’t think the war was right and he just wanted to go back to New York and play music in his rock band. And I kind of sympathized with him, but I wasn’t ready to do what he did, because he took a lot of verbal and physical abuse. I mean, they made him lay down face down on the ground at the position of attention, and then they stood over top of him and called him all kinds of, you know, names — faggot, queer, everything that would be counter or against the whole idea of masculinity, you know, called him a coward. But he just stood there expressionless. And there was some physical abuse too. That experience of watching that trainee go through the kind of hell that he went through, standing up for his sense of right and wrong, was something that stuck with me, and when I got to Oakland, I guess my reasons for considering going AWOL or deserting was watching him go through what he did. But also, you know, I knew that there were a lot of guys, including myself, who hated being in the Army.

Willa Seidenberg 11:34

Okay, so what happened as you were making your way to the Oakland Army Base to report for service.

William Short 11:42

When I was walking from the hotel to the base, which I think was probably maybe four or five blocks from the base, I passed this church along the way, and I thought, I’m going to go in and see what’s going on in kind of my heart and mind. I wasn’t particularly religious, but I went there, I guess, looking for somebody to make the decision for me about whether I was going to go or whether I was going to desert. So, I sat in the pew for, I don’t know, must have been maybe an hour. I was thinking about my dad, you know, coming to my graduation, and then crying when he saw me board the plane. I thought about how he might be disappointed in me. And so I decided, well, okay, whoever’s up there, help me do the right thing. I’ll go and see it firsthand for myself, and if I think that it’s wrong when I get there, then I’ll figure out what to do about it when I get there. Pretty naive thing to do. I had no idea what I was going to do when I got there. I just knew that I would figure out something if I disagreed with, you know, what I saw when I got there,

Willa Seidenberg 13:06

So, what made you decide to actually leave your dog tags?

William Short 13:10

I don’t really know why I left my dog tags. It wasn’t planned or anything. It wasn’t thought through. As I was getting up to leave, I just spontaneously took my dog tags off and hung them on one of the crosses. I did that and then walked out of the church and left that part of me back in Oakland, hoping that somehow that would protect me.

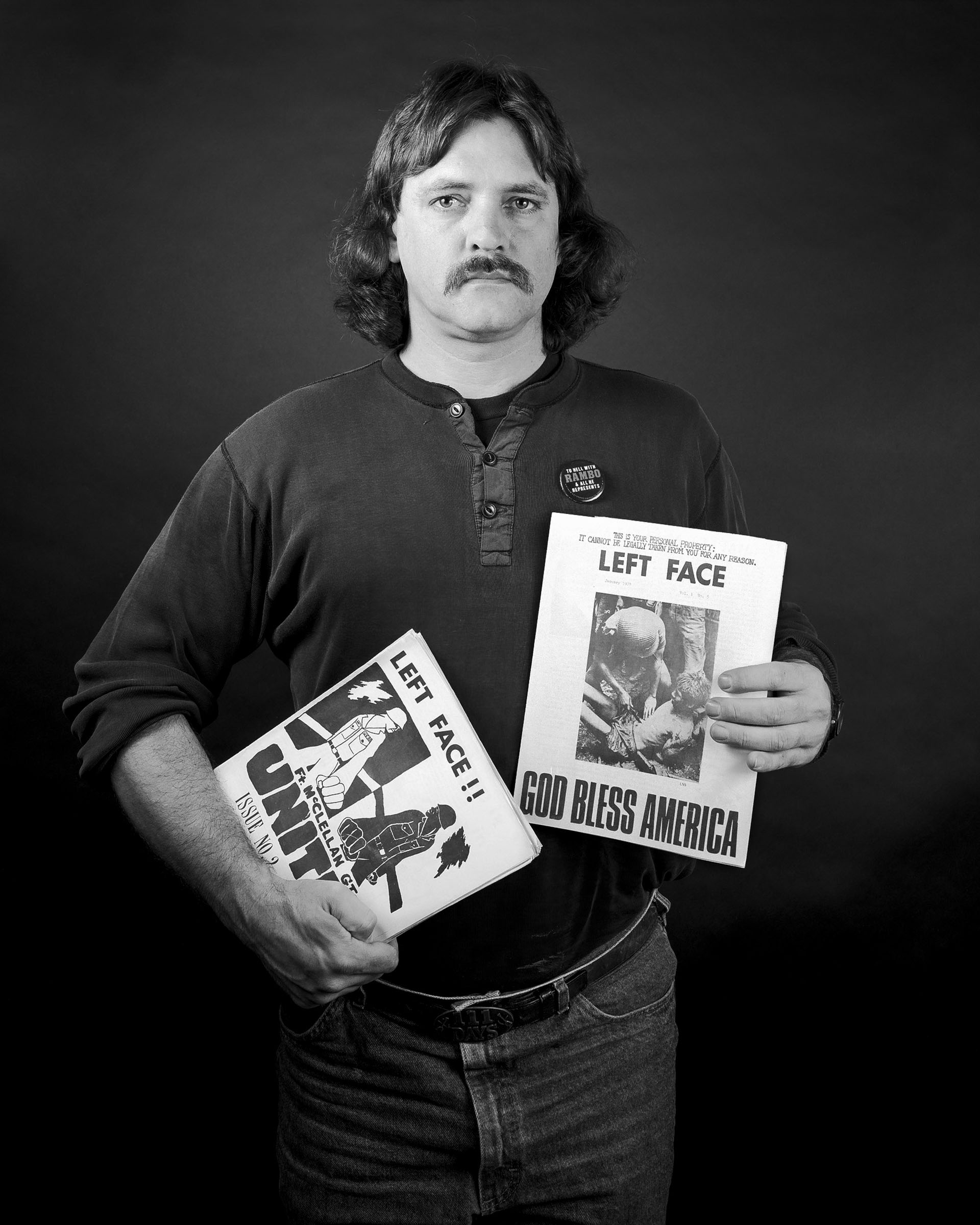

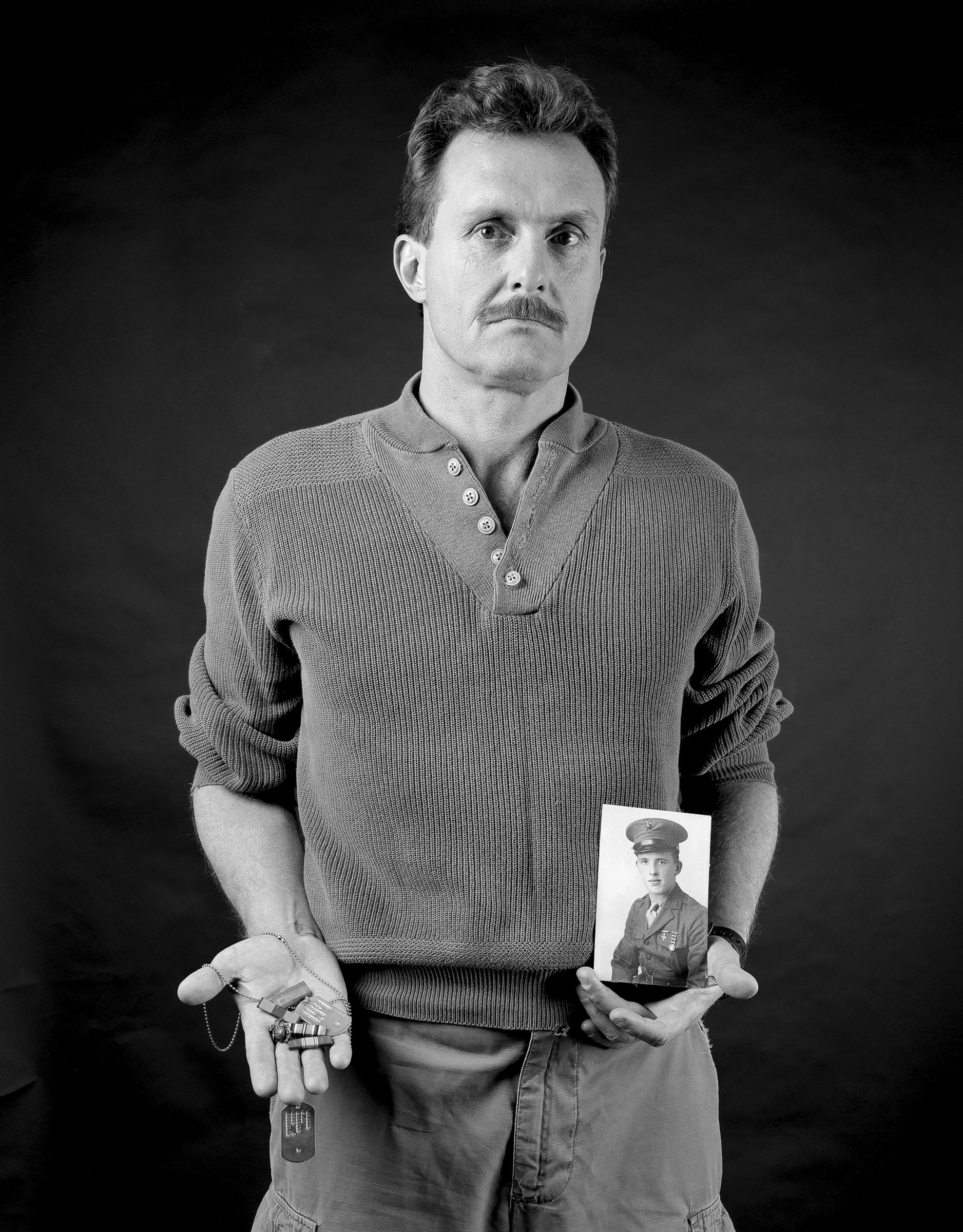

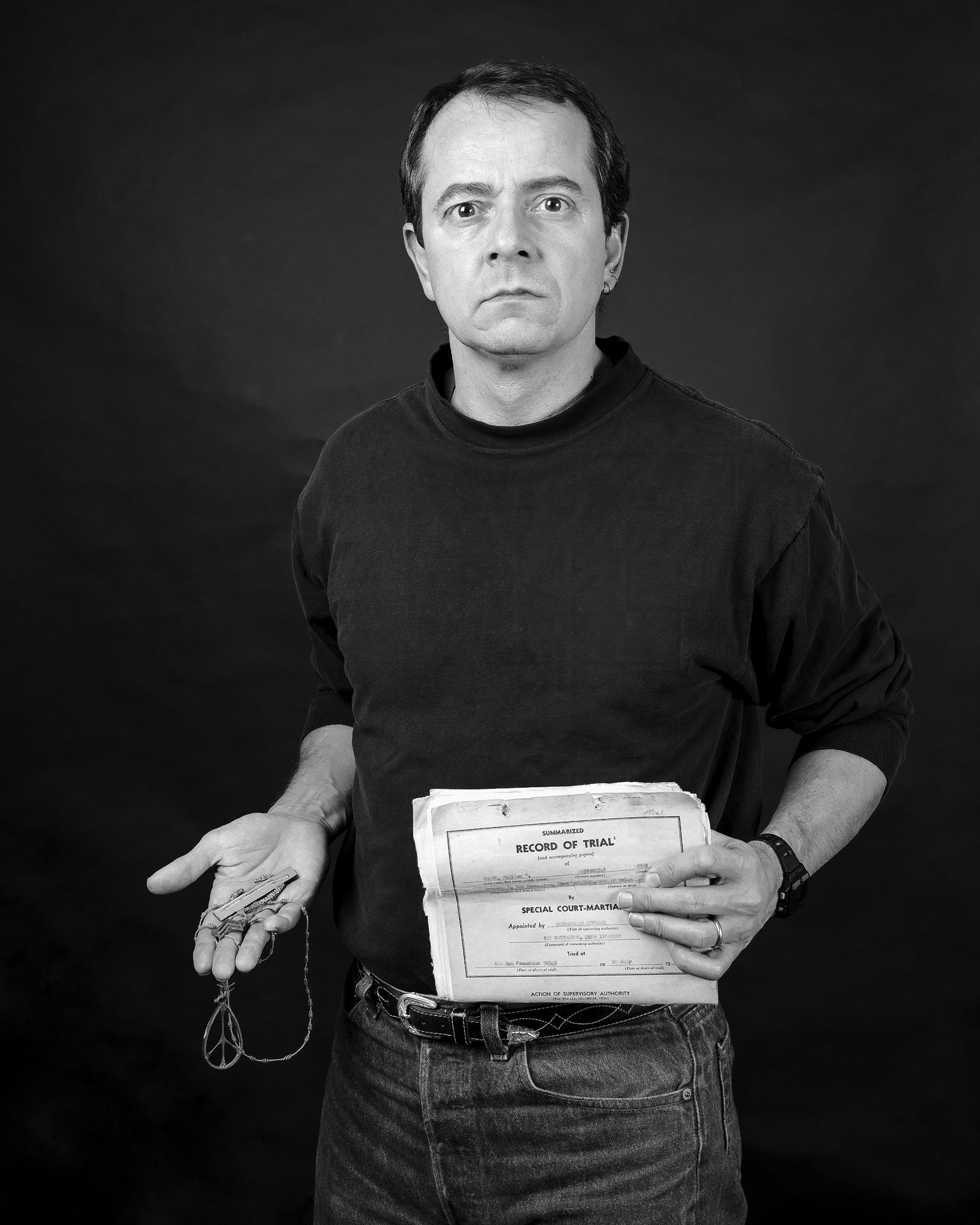

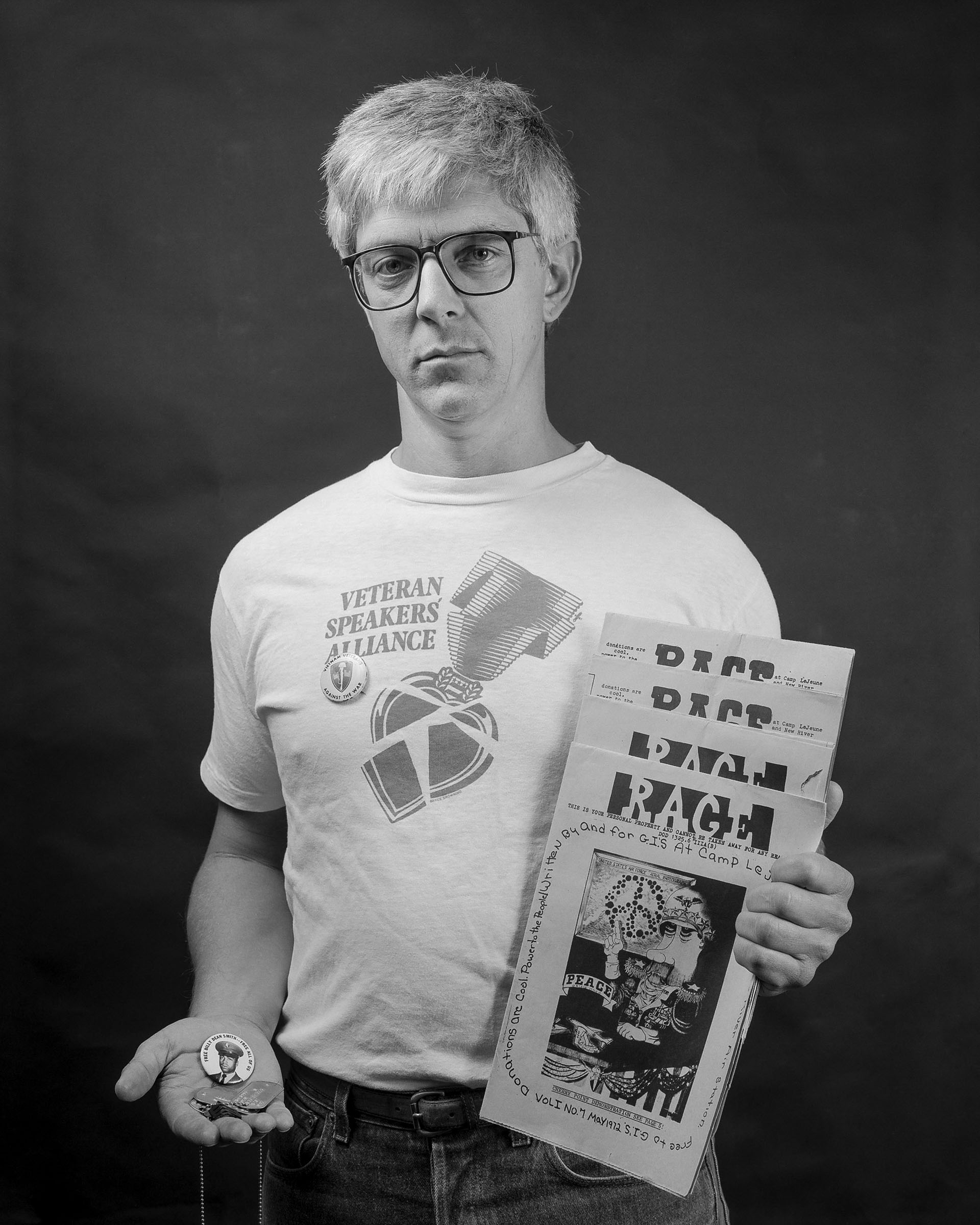

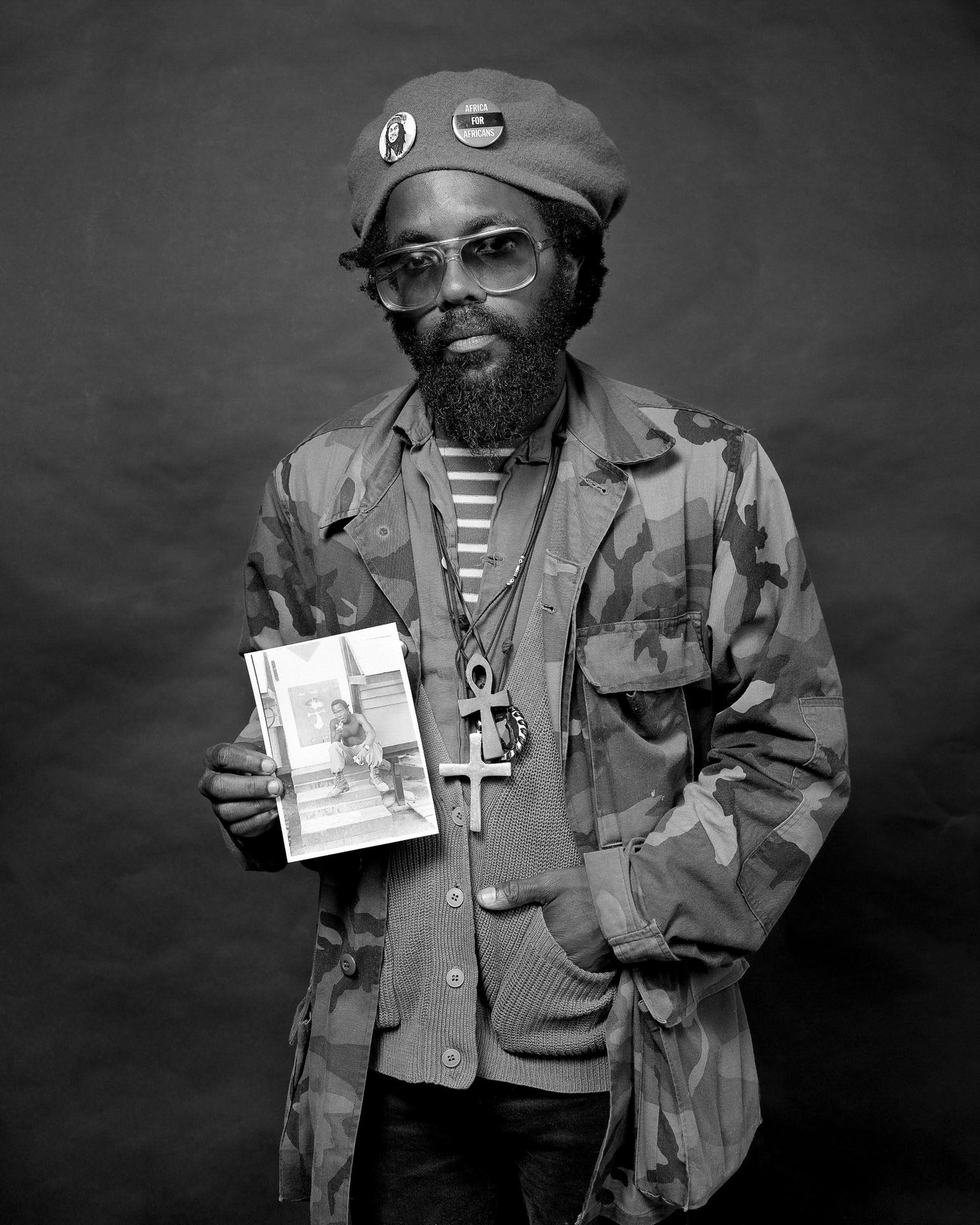

This podcast is based on an exhibition and book we published in 1992. I started photographing and interviewing other Vietnam GI resisters I met in Boston in the late 1980s.

Willa Seidenberg 14:09

So, we keep bringing up this term, GI. Bill, what does GI stand for?

William Short 14:15

GI stands for government issue, you know, like an article of clothing or maybe even a toothbrush, or a guy who’s going to be a soldier. Something or somebody who is expendable. In fact, during basic training, we were told by our drill instructors that we were indeed expendable, that it would cost more to replace our M 16 rifles if we dropped them in the dirt than replacing us if we drop dead in the dirt.

Willa Seidenberg 14:41

Yeah, that’s the message Lamont Steptoe got. He was a dog handler in Vietnam.

Lamont Steptoe 14:47

You go out on a mission, the max time you can spend on a mission is seven days before that dog has to come back because that dog’s worth $30,000. They care more about that dog than they do you.

Willa Seidenberg 14:58

For more on the GI movement we turn to someone who spent his career writing and teaching about the Vietnam War.

Chris Appy 15:08

I’m Chris Appy, I’m a professor of history at the University of Massachusetts and the director of the Ellsberg Initiative for Peace and Democracy. I grew up in just the wake of the Vietnam generation, and turned 18 the year the draft ended, and the year the final American troops were withdrawn from Vietnam. Even so, I felt as the war was going on, kind of the undertow of its moral and political pain, even though I felt quite safe from the war and lived in a community where I knew not one person who was fighting in the war, or even anyone who was deeply involved in the anti-war movement. It nevertheless felt like a sharp moral turn for the worst for the country. And so when I went off to college, I actually felt a kind of moral obligation to learn things about the war that I just intuited but didn’t really have any fundamental knowledge about, and that led me, in graduate school to further pursue it.

Willa Seidenberg 16:13

Chris is just a few years younger than me. I spent my high school years going to demonstrations against the war. I was in college by the time the war officially ended. At the time, I didn’t know anything about the anti-war movement within the military, which Chris calls a “secret history.”

Chris Appy 16:37

Particularly in the Reagan years of the 1980s, there was a quite concerted effort to demonize the anti-war movement in all its forms. And one way to do that is to suggest that basically, the anti-war movement was a bunch of sort of cowardly, self-righteous hippies who reviled the military and everyone who served in it. And then you had on the other side of this generation, these brave, patriotic, heroic men who went off to Vietnam and fought.

Willa Seidenberg 17:08

Here’s former President Ronald Reagan speaking to a veterans’ convention in 1980.

Ronald Reagan 17:15

There’s a lesson for all of us in Vietnam, if we are forced to fight, we must have the means and the determination to prevail, or we will not have what it takes to secure the peace. We will never again ask young men to fight and possibly die in a war our government is afraid to let them win.

Chris Appy 17:38

The reason the United States failed in Vietnam was not for lack of arms or lack of lethality and destruction. God knows, the country was devastated. More than three million people were killed. The reason for the failure was that the government we supported never had the sufficient political support of its own people. The effort to shame anti-war activism is very useful in a presidency that’s trying to ratchet up Cold War hostilities and wage proxy wars in Central America and to demonize communism everywhere.

Music: Fortunate Son/Creedence Clearwater Revival 18:12

William Short 18:33

This song, “Fortunate Son” by Creedence Clearwater Revival is historically significant. It’s a critique of the draft system that allowed those of wealth and class to avoid serving in the military.

Soldiers were either drafted like I was, or enlisted. Those who enlisted often became the most outspoken against the war. They joined the military willingly because they believed what they were told about the war, and wanted to fight for their country for what they thought was a just cause.

Music: Fortunate Son/Creedence Clearwater Revival 19:02

Chris Appy 19:19

Most of them were working-class guys who came from families that had served in the military. Very patriotic.

Army recruiting ad 19:25

Your man in Vietnam, James Daly, specialist 6, United States Army.

Chris Appy 19:32

And went off to this war where they quickly discovered that they had been sold a bill of goods.

Army recruiting ad 19:39

Who trusts a 26-year-old with the care and feeding of a million dollars’ worth of equipment — the United States Army.

Chris Appy 19:45

Their own experience made clear to them that the people of South Vietnam were not greeting them as liberators, and the troops ordered to carry out these missions understood how destructive their own military’s actions were for ordinary Vietnamese people. And they increasingly came to feel that they were being used and actually betrayed.

Music: Kiss My Ass/Country Joe McDonald 20:10

Chris Appy 20:26

American troops, I think even early on, were disillusioned about the war, but didn’t really act on it with open defiance and dissent until later, and that’s completely understandable. And one thing that we have to remember is that this most extraordinary movement of active-duty soldiers happened in an authoritarian institution, that’s to say the military, which has an endless number of ways to enforce obedience and to punish dissent, everything from forced work and exercise to imprisonment, court martials, demotion, dishonorable discharge. I mean, you name it.

William Short 21:13

And that includes intimidation. Dennis Stout reported war crimes that he witnessed when he was a soldier in Vietnam. When he came back, he received intense harassment from the Criminal Investigation Division, or CID, just as he was about to give a speech in Phoenix, Arizona.

Dennis Stout 21:30

And the night before I made the speech, two agents again with CID identification, came to the house and with my wife standing in the living room, they said, “We hear you’re going to make a speech tomorrow at the federal building.” And I said, “Yes.” And the agent said, “If you make that speech, you know that you could go to work some morning and disappear, and no one would ever know what happened to you.” And then he took his finger and poked me really hard in the chest and said, “And you know, we can do it too, dontcha?” And you know, I figured he really could.

William Short 22:15

Even the military brass knew there was a problem. In 1971 Colonel Robert Heinl wrote an article for the Armed Forces Journal. It was called The Collapse of the Armed Forces. These are his words. Quote: “The morale, discipline and battle worthiness of the U.S. armed forces are, with a few salient exceptions, lower and worse than at any time in this century and possibly in the history of the United States. By every conceivable indicator, our army that now remains in Vietnam is in a state approaching collapse, with individual units avoiding or having refused combat murdering their officers and non-commissioned officers, drug-ridden and dispirited, where not near mutinous

Chris Appy 23:13

It took every sort of form, from individual acts of disobedience to collective efforts, to start anti-war newspapers to conduct boycotts, hunger strikes, form radical reading groups, to wear anti-war insignia on uniforms, and most extremely, but not uncommonly, to actually refuse to fight, to mutiny, to disobey direct orders to walk down this trail or search this tunnel. Even pilots toward the end were beginning to refuse combat missions.

Willa Seidenberg 23:55

Whether or not they acted on their feelings while in the military, many soldiers came back from their service and took part in the anti-war movement.

Chris Appy 24:05

And did so in a way that was extraordinarily dramatic and captured the attention of the nation in a number of different demonstrations, particularly when hundreds of veterans lined up in front of the United States Capitol,

Archival audio: Dewey Canyon III 24:20

I pray the time will forgive me and my brothers what we did, and only those lumping pigs…

Chris Appy 24:24

And threw away the medals and ribbons that they had received for valorous conduct in waging war in Vietnam. And would make public statements denouncing the war and saying that they they could feel no pride or honor in continuing to hold on to these awards.

Willa Seidenberg 24:46

What Chris is referring to is Operation Dewey Canyon III. It was organized by Vietnam Veterans Against the War in April of 1971. VVAW named it after the Operation Dewey Canyon military action. In that operation, the U.S. and South Vietnamese forces made incursions into neighboring Laos and Cambodia.

Archival audio: Dewey Canyon III 25:10

Robert Jones, New York. Likely return all Vietnam medals and other service medals given me, given me by the power structure that has genocidal policies against non-white peoples of the world.

Chris Appy 25:24

That was striking, because you couldn’t dismiss these veterans as cowardly hippies. You know, these were people who had made the greatest sacrifice and decided that it had been wrong. So, they had a kind of moral authority that other members of the anti-war movement didn’t. Many of them who were campus-based were protected from the war by student deferments and so forth. It did inject at a key time when a lot of other people in the movement were disheartened and frustrated, and the war keeps dragging on, it infused a new level of energy and drama into the movement. And I think probably helped convince a lot of Americans who had been on the fence that something is deeply troubling about this war. I think a lot of older Americans too,

William Short 26:19

Even my father, who worked for Air Force Intelligence, eventually came to believe the war was wrong.

Chris Appy 26:25

And maybe older World War II veterans, they would maybe try to dismiss or criticize these younger veterans, but it troubled them. It troubled them the stories that they were telling.

William Short 26:38

When I was in Vietnam, I had to balance staying true to my moral compass with what was expected of me by my commanding officers. That was true for so many of the veterans we interviewed, like John Tuma. He was an Army interpreter. When he was part of interrogations, he refused to allow Vietnamese enemy prisoners to be tortured by South Vietnamese forces that were allied with the U.S.

John Tuma 27:03

I remember I used to think, what would my parents have done? What would be the right thing to do? Not the right thing to do from an army point of view, but what’s the right thing to do with my own family, my own community’s morality and things like that? I consciously thought about that and came to the conclusion that were things that I had been raised not to do and I would not do.

Willa Seidenberg 27:38

This idea of following orders or following your conscience was brought home in the aftermath of World War II, during the Nuremberg trials. That international tribunal prosecuted German political and military leaders for crimes against humanity. Some of those on trial used the defense that they were just following orders and therefore not personally responsible for their actions during wartime. Sir Hartley Shawcross served as the lead British prosecutor at Nuremberg. He made a distinction between just and unjust wars.

Hartley Shawcross 28:16

Political loyalty, military obedience are excellent things, but they neither require, nor do they justify the commission of patently wicked acts. There comes a point where a man must refuse to answer to his leader if he is also to answer to his conscience.

Willa Seidenberg 28:48

Many women in the military also had to answer to their conscience. Susan Schnall was a Navy nurse at the Oakland Naval Hospital in Oakland, California. She was treating soldiers who had been injured in Vietnam.

Susan Schnall 29:03

There was a point at which it was obvious that I had to do something about the war, that I was no longer patching up people to feel better, but that I was promoting the war machine. And there was a point at which I just said, Look, I can’t deal with myself anymore. I absolutely can’t live with it. All I’m doing is promoting the war. And it was about that time that I heard about the GI and Veterans March for Peace in San Francisco.

William Short 29:30

Susan and many other GIs took a public stance against the war, but behind the scenes, there are many small acts that took place daily. People like Alan Klein, who was in the Air Force in 1966. He and others in his unit, made a pact to gum up the works of the war machine.

Alan Klein 29:49

And we decided that what we could best do is to destroy, to the best of our ability, without being too flagrant about it, the efficiency of our outfit. This is just sort of like the classic notion of foot-dragging resistance. Some people resist outright, in an informal way, but most of resistance, it turns out, is this of the sort that we sort of independently came upon. And we started by little things. We started dressing like shit. We wanted to make sure that nobody in our little sector, and our circle of influence was growing, would ever dress right so we could ever pass inspection. What would it be like to be an officer going down the ranks, inspecting your men, and none of them could get their gig lines straight, none of them gave a shit about anything. And we started with poor job performance. We started fucking up on the job. We started damaging things on the job. You know, little things, wasn’t too overt.

William Short 31:15

Next time on A Matter of Conscience, we’ll explore how World War II affected the young men who became the Vietnam generation of soldiers.

Paul Atwood 31:24

My own father called me a traitor. I was in a straitjacket and a padded cell. My father appeared standing over me, and he said, You are one pathetic piece of shit. You harmed the family name. It still gives me the willies.

Steve Spund 31:42

People who had finished at least one tour of Vietnam, were coming back and telling me what was going on there totally contradicted everything that I believed in.

William Short 31:52

We’ll hear the stories of marine veterans Paul Atwood and Steve Spund.

Willa Seidenberg 32:01 This podcast is independently produced with crowdsourced funds. We thank the dozens of people who donated, and you can join them by going to our website amatterof conscience.com. You can also see a glossary of terms and show notes for this episode. This episode was produced by Willa Seidenberg, Bill short and Paulina Cherezova, Dylan Purvis is the associate producer. The assistant producers are Ruben Flores and Aubrey Jones. Many thanks to Country Joe McDonald for giving us permission to use his song as our theme music. Original music is by Danny Seidenberg. Sound Design by Paulina Cherezova. We thank the Kazan McClain Partners Foundation for their generous support. Our fiscal sponsor is the International Documentary Association. Thanks also to Denise Abrams, Chris Appy, Bill Belmont, Danny Bringer of KQED radio, Judy Muller, Tena Rubio, Sam Short, Veterans for Peace, and David Zeiger. And finally, our gratitude to all the veterans who shared their stories with us.