I joined the Army in February 1967. I got to Vietnam in May, and by August I was very clearly against the war and against the military as well. I think for most soldiers, going to Vietnam and seeing the reality of the war, all this mickey mouse bullshit as the whole army was, to actually be in the middle of a war where hundreds of people were being killed everyday, it was just incomprehensible to most of us. I think most of us just immediately opposed that and maybe our understanding of why we opposed it wasn’t as sharp as it might have been, but just on a gut level. Having been raised like myself, a Presbyterian, and being active in the church in the area I grew up in, it just wasn’t right what was going on in Vietnam. While I was in Vietnam I didn’t see any way to take action against the war, so my own response was basically to withdraw from any kind of overt activity that promoted the war.

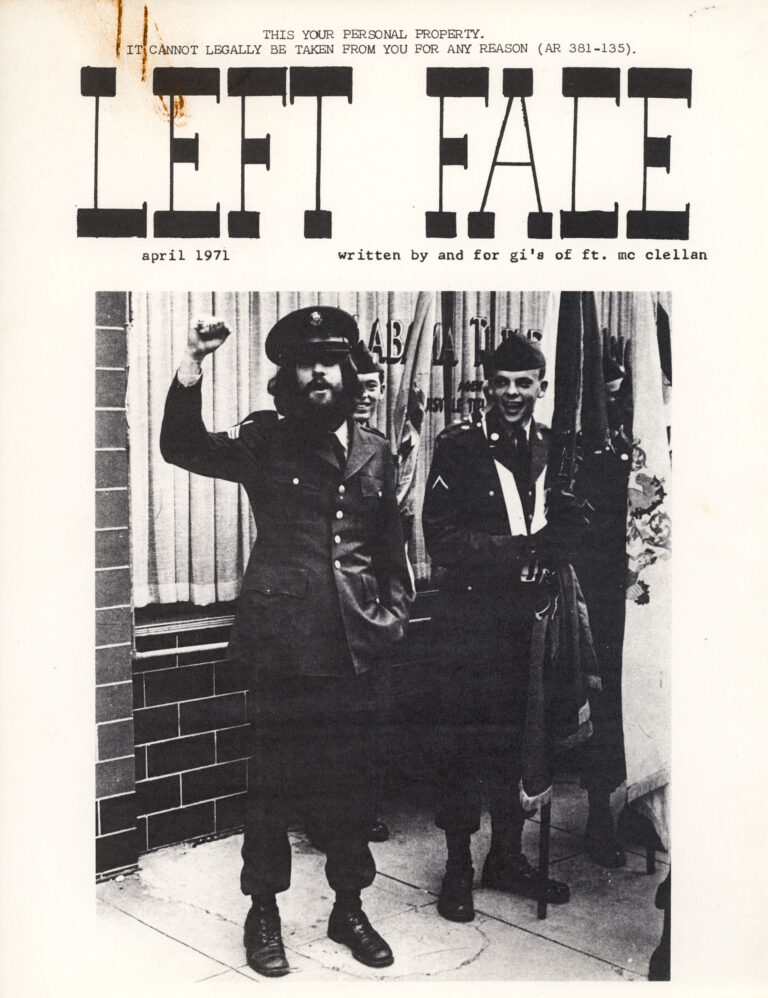

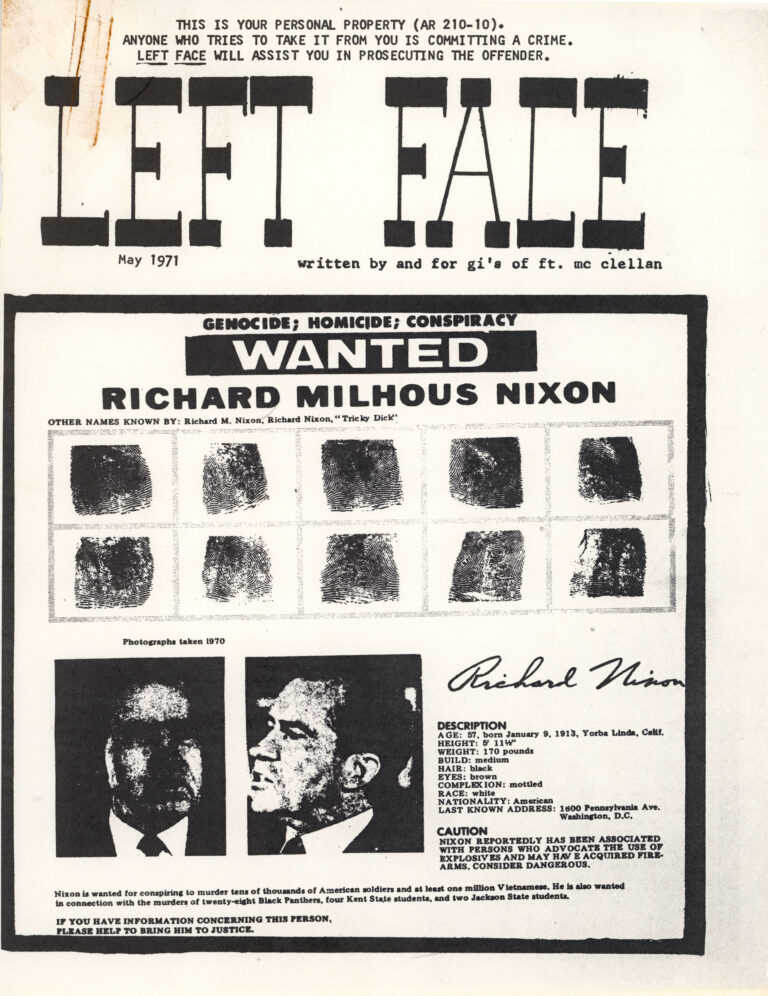

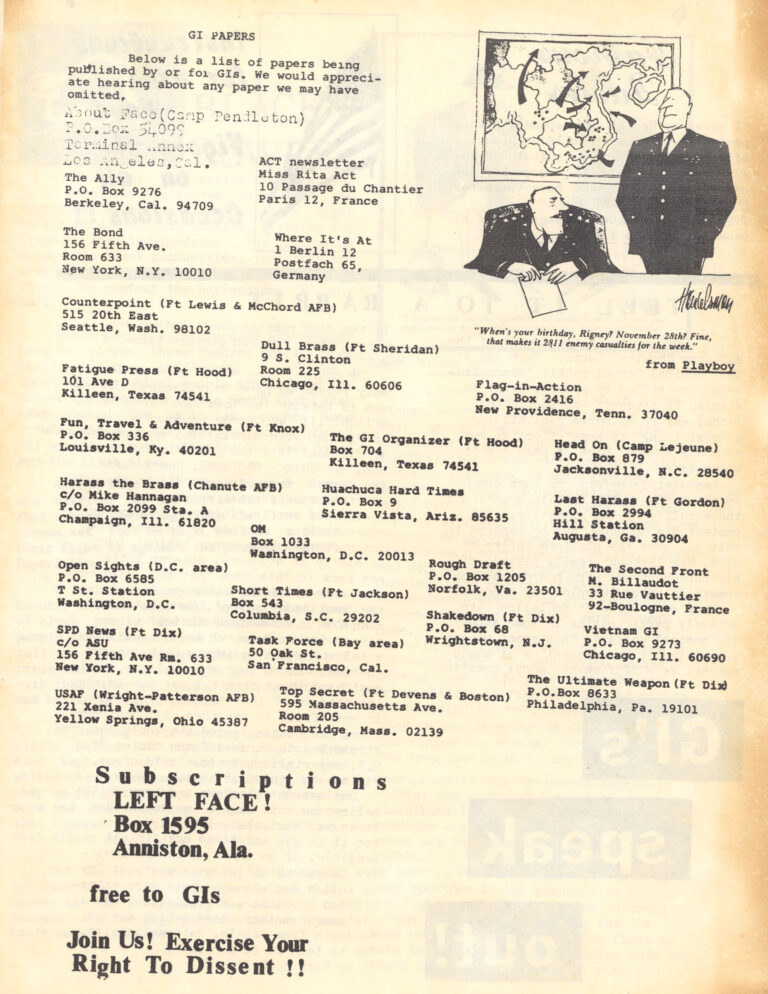

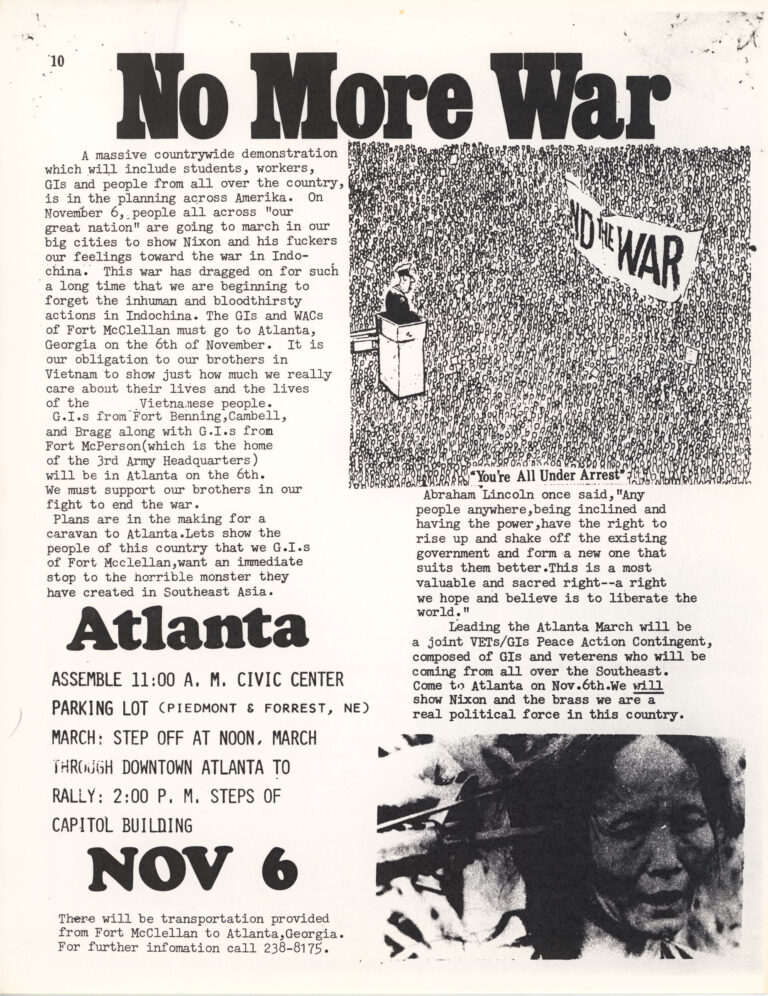

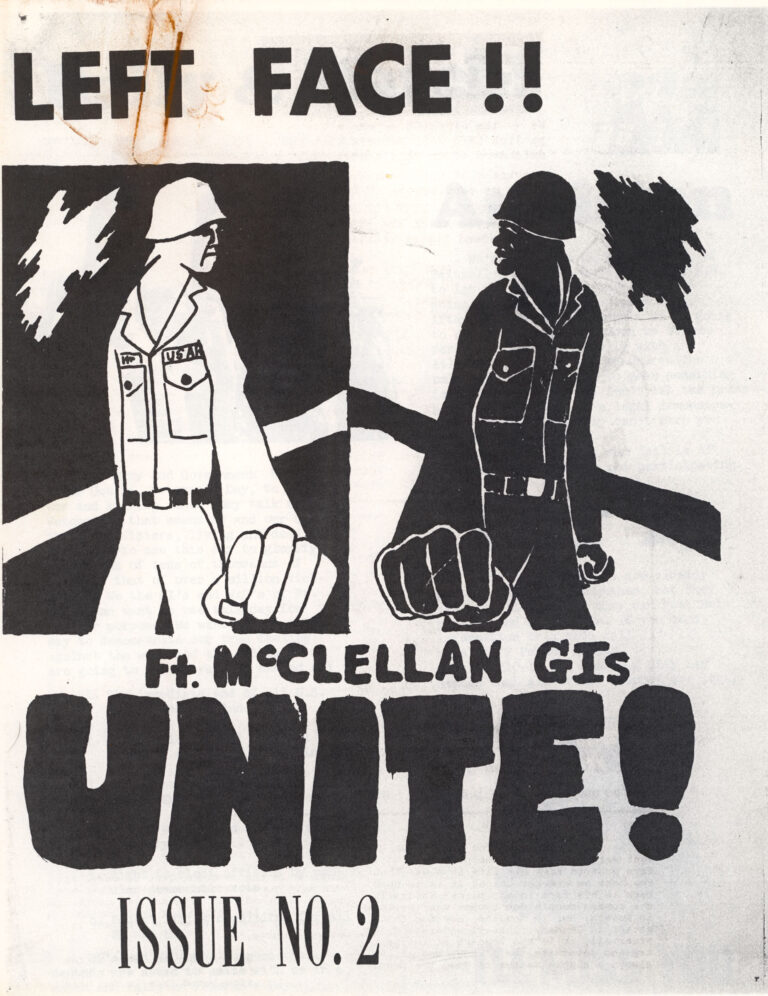

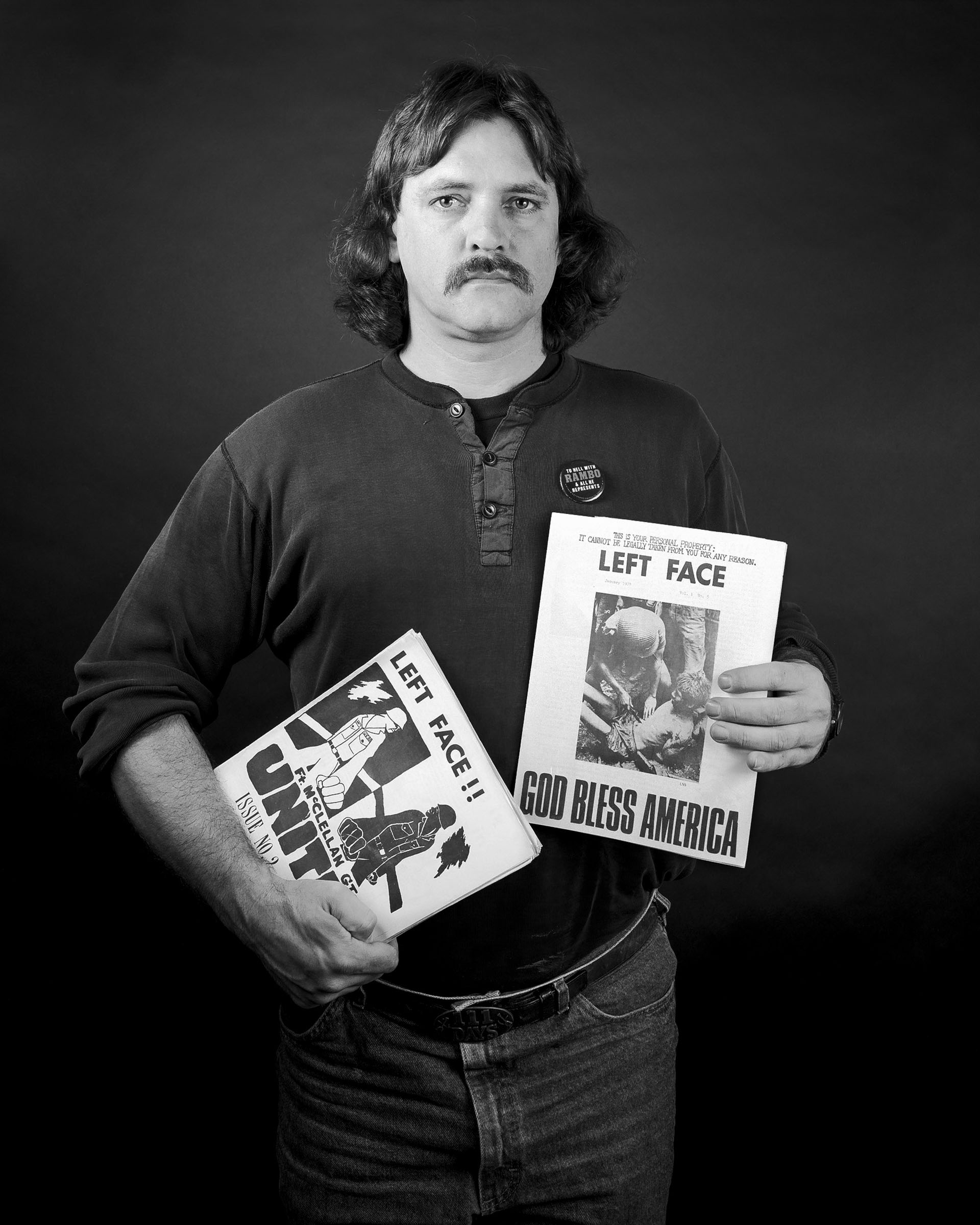

I came back very committed to fighting this whole machine that sent us there and kept us in Vietnam. I came back with six others who got assigned to Fort McClellan, Alabama — this is where I had taken my training to be a chemical repairman before going to Vietnam. We decided we wanted to try to take some action against the war and decided to put out a paper. I started going up to Atlanta where there was very vibrant youth culture on the streets and an underground newspaper called A Great Speckled Bird. I got in touch with some people there who turned me on to somebody who could print the paper for us, and met a guy, another GI who had some experience writing and working on a college paper.

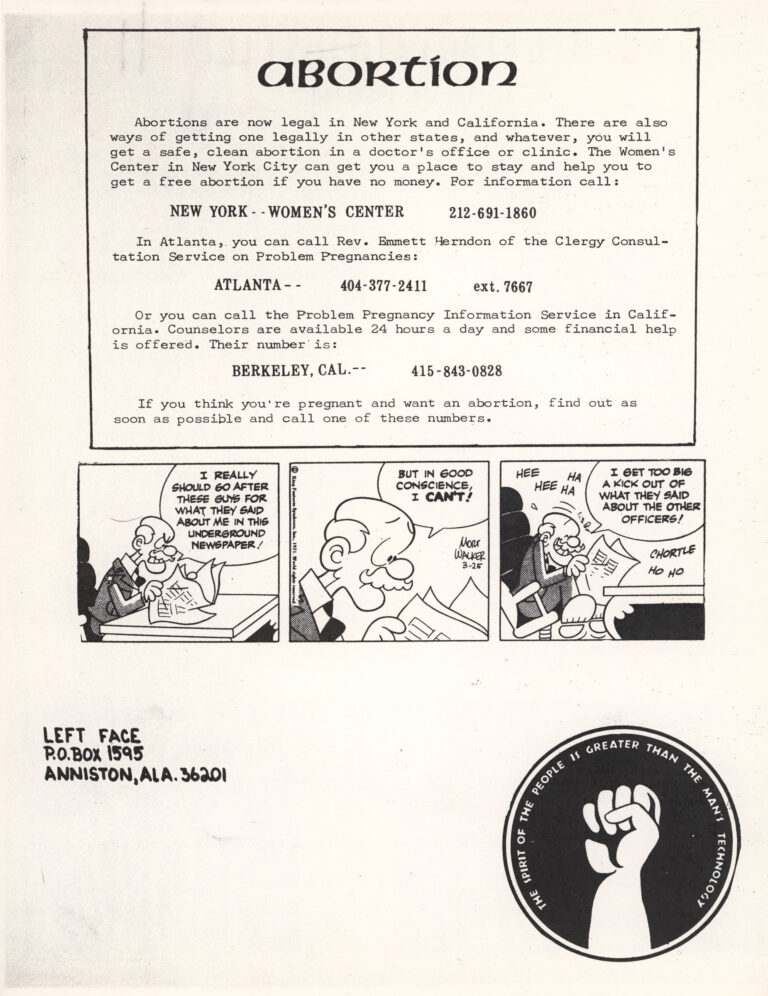

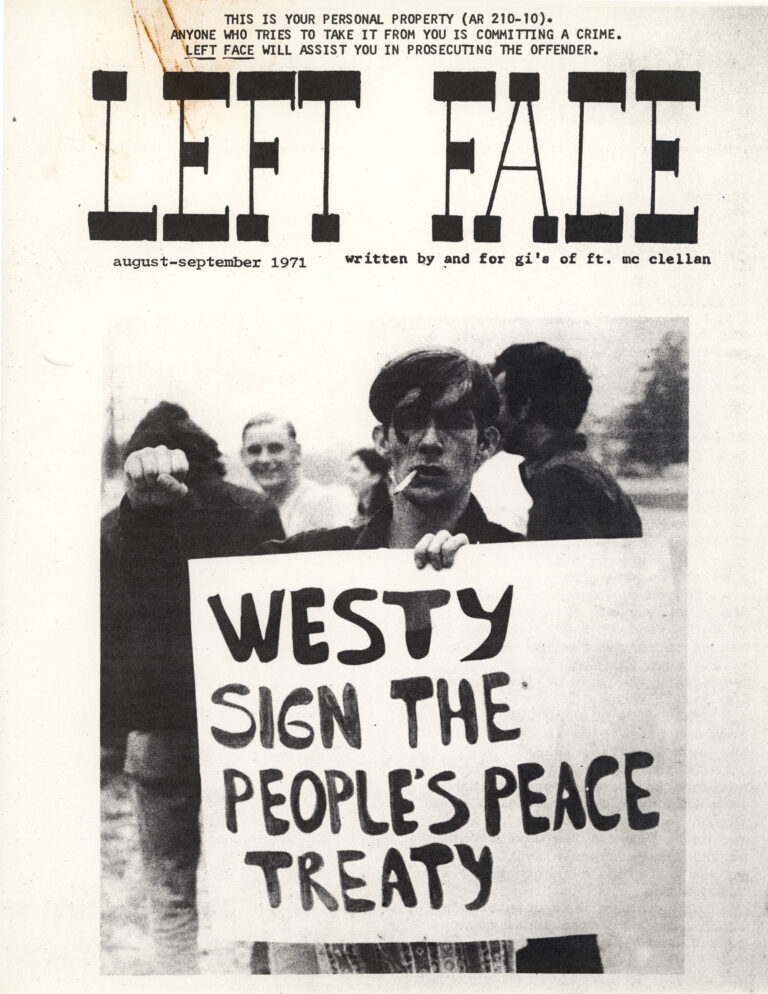

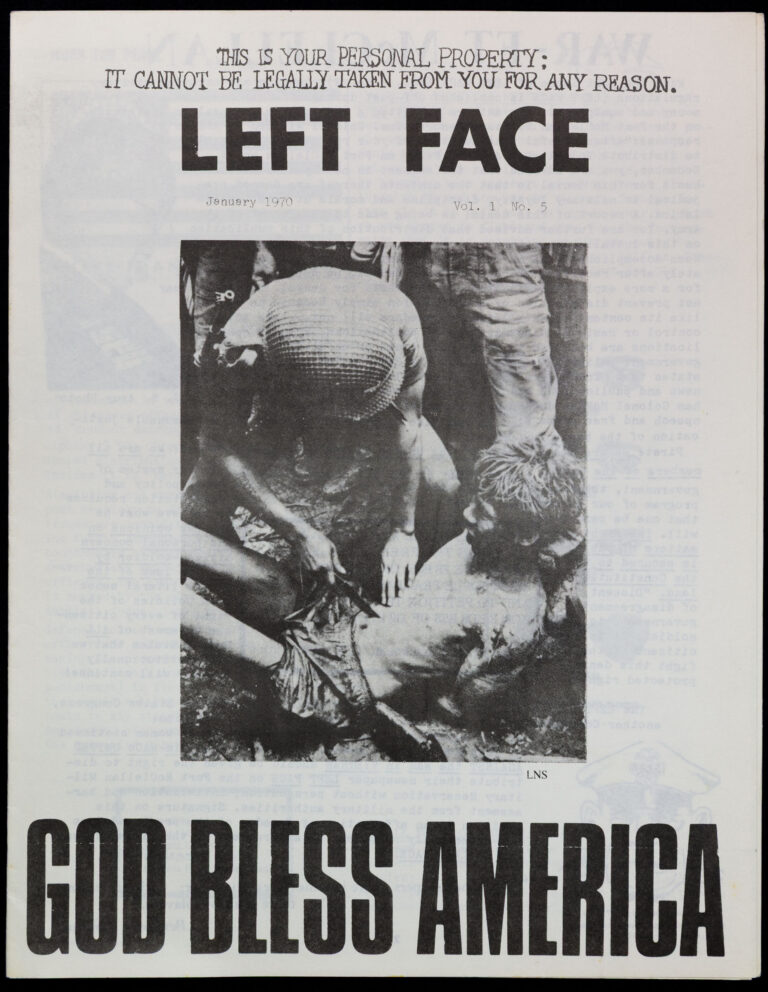

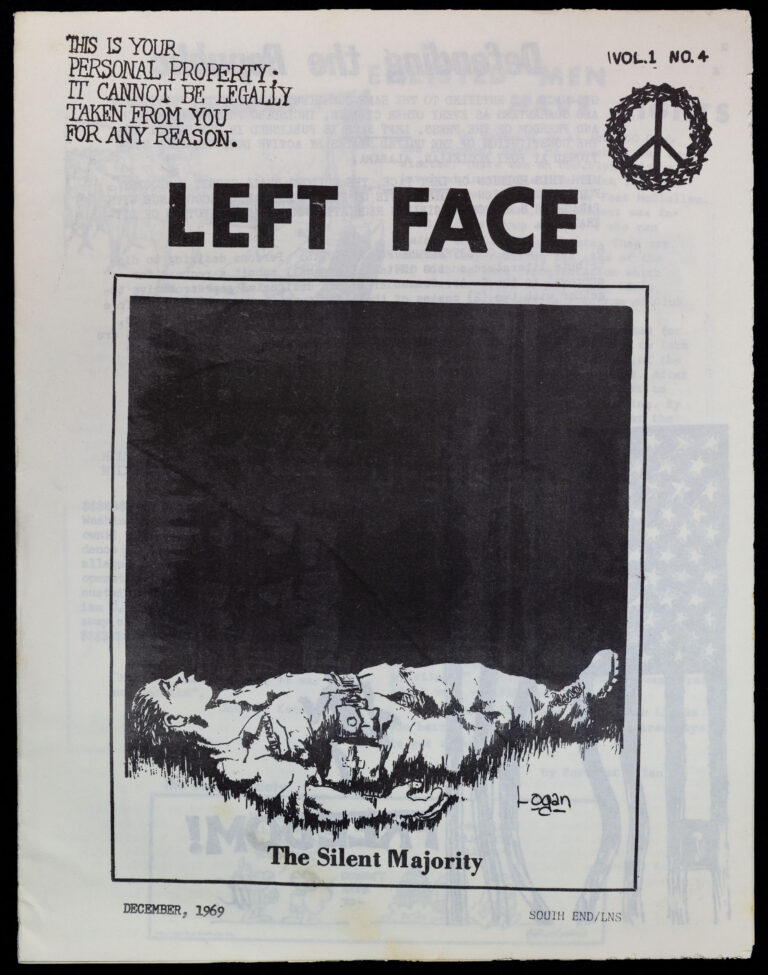

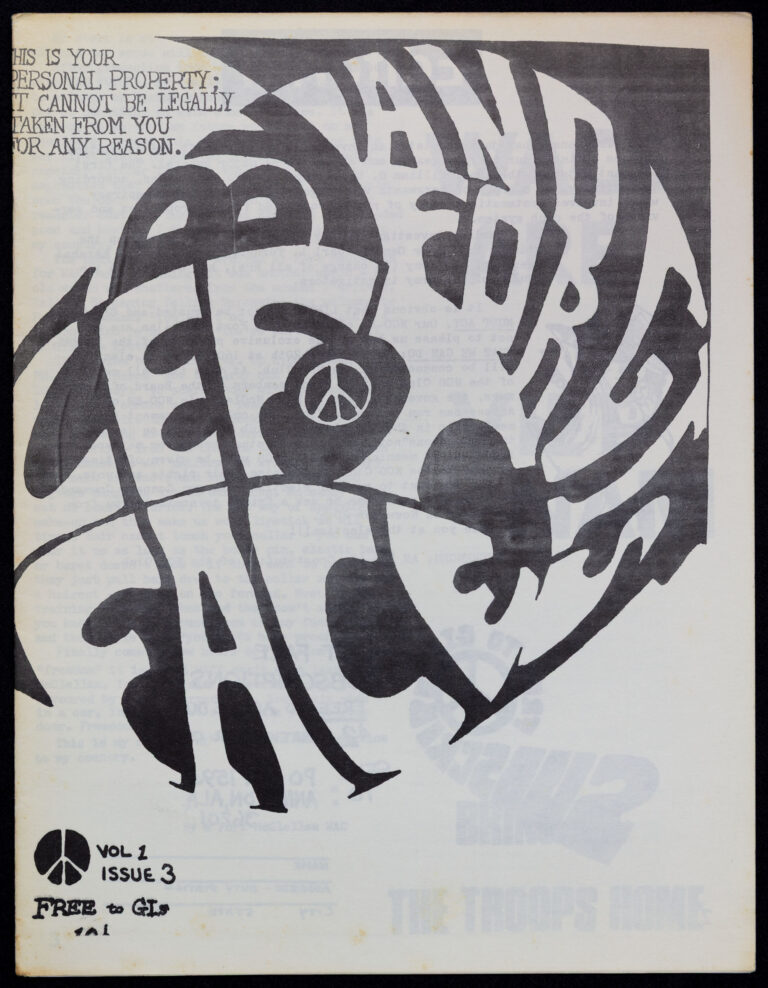

Somehow it all just came together and we started putting out a paper, which we called Left Face because I guess, though we were all pretty inexperienced with politics, it was real clear that our views were always to the left and that’s where we were looking to — the Left. We’d have to spend a fair amount of time figuring out how to get the paper out, into hands of people on the base. You’d sneak around at night and you’d run in barracks and you’d throw it on the beds and you’d split and get the hell out of there. I can remember running out and jumping into the trunk of a car and laying in the trunk; the MPs would come and you would be hiding in the trunk of some cars and hoping you wouldn’t get caught. Because if you got caught, you could get six months in the stockade, the potential punishment for distributing unauthorized literature, which the papers were characterized as.

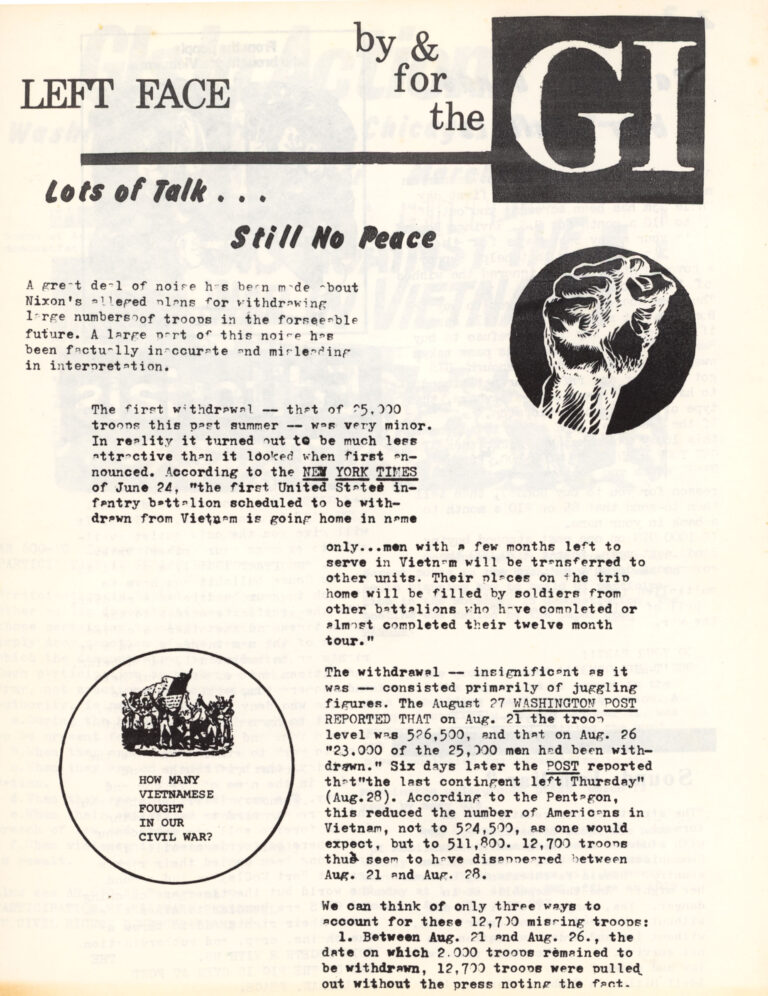

Immediately after we put out the first paper, in late October of ’69, about 30 of us on the base signed a petition being circulated by the GI Press Service in support of a demonstration coming up on November 15th in Washington. As soon as it appeared in The New York Times, it was sort of like all hell broke loose on that base because people’s names were on that ad. Everybody who signed it got called in by Military Intelligence and interrogated and harangued and people lost their security clearances and things like that. I thought and believed very much that since I had been in Vietnam, I had every right to comment on it to other people. In fact, I had a responsibility, and I took it seriously. I thought it was my democratic right to speak out and I was really shocked to find out that wasn’t reality or freedom in America.

Archived Material

Podcasts

No posts