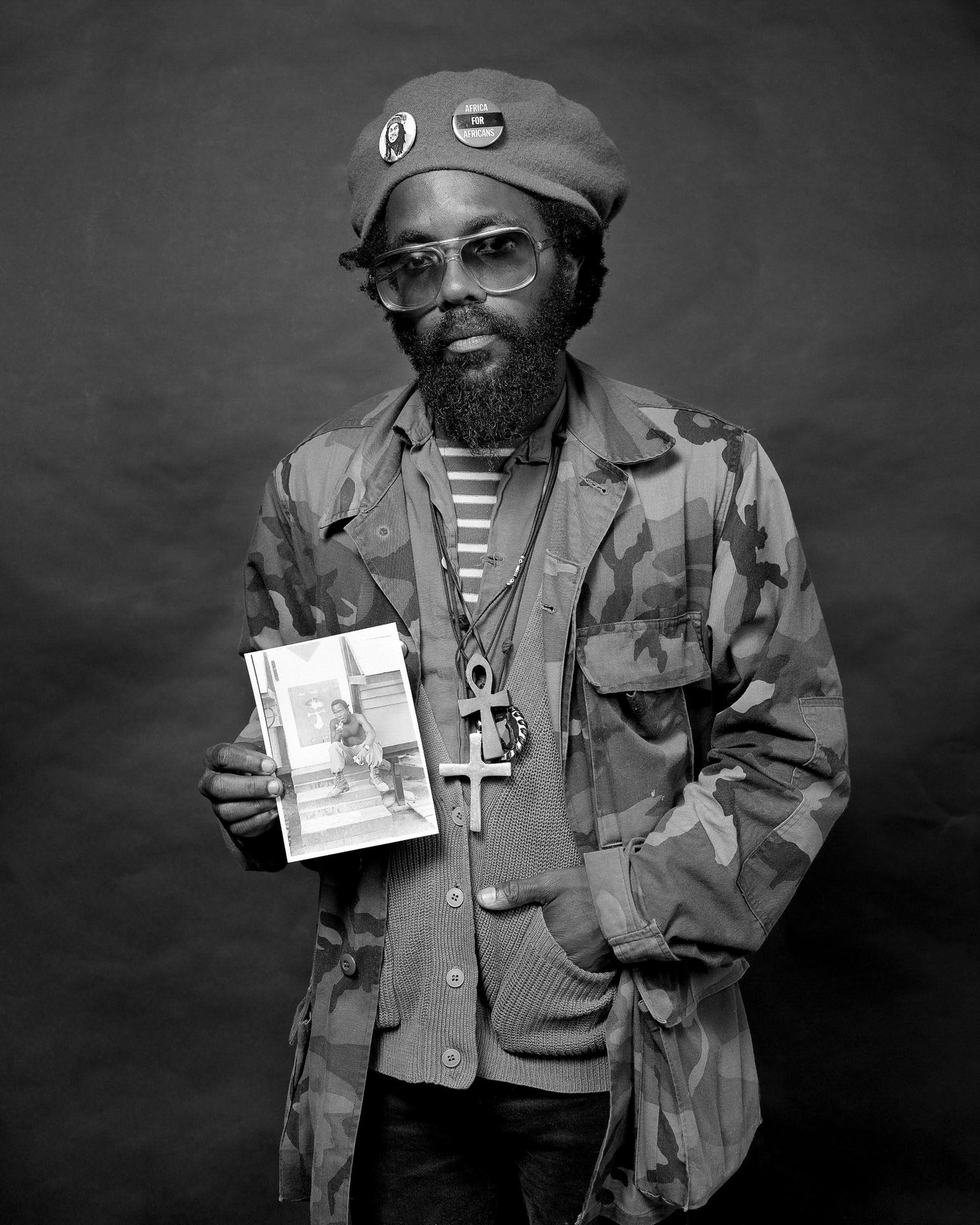

The racist comments by the veterans who were training us in Officer’s Candidate School (OCS) — them saying the word gook and mocking Vietnam as a ‘live fire’ problem — made me uncomfortable. An incredibly high percentage of Afro-Americans in the infantry were dying on the frontlines. As these statistics about blacks in Vietnam began to roll in, I would talk to other black GIs returning from Vietnam. They would tell me stories about the unity of blacks in Vietnam, and all of this made me think.

I was called before a board of officers for my complaining about being treated a certain way by some of the cadre because I was black. The officers were sitting there denying that there was any racism, despite me telling them over and over about instances where I felt I was treated differently than the white soldiers. Repeatedly all the white officers told me there was only one color in the military: olive drab.

I began to have a bad attitude. Sixteen of us resigned from OCS, all within two weeks, because we just didn’t want to take it anymore. We were told that if we quit OCS we would be punished. And they kept their word. If you fucked up in OCS, they sent you to a leg unit.

I got orders for a scout dog unit, which meant that I was going to walk point in Vietnam. I was freaked out, terrified of dogs. There were very few blacks in scout dogs. I guess I was lucky because they could have sent me straight to a military unit, to the frontlines, where I would have spent 364 days in the field. But with a dog the max time on a mission is seven days, because that dog’s worth $30,000 and they care more about that dog than they do you. But it was a very dangerous job.

I’ll never forget the look on a family’s face when we searched a village one time and this lieutenant ordered me to kick in the door. On the other side was a family eating dinner. My dog jumped on the table and the family was terrified and shrank back against the wall. We ransacked the house and decided they had too much rice, so we took it. Things like that began to bother me and I began to be very angry toward the military and what we were doing.

I read the Autobiography of Malcolm X in Vietnam and it had a very strong effect on me. I wrote home and told my mother that I was going to become a Muslim after reading that book. It really gave me a sense of where I stood in relationship to the military, in relationship to America. I began to identify with the Vietnamese. The hootch girls would tell me, “you same-same us.” I began to have this feeling for the Vietnamese people. I felt I was living this contradiction of being a Black soldier in the land of another man of color and terrorizing him. I never allowed myself to call them gooks. Muhammad Ali said it so clear, “ain’t no Vietnamese ever called me a nigger.”

On the anniversary of the assassination of Malcolm X, I convinced the other blacks in my unit to turn out with black armbands. It polarized the unit because the white soldiers were taken aback. There were only a few of us blacks and [the white guys] thought we were friends. And we were in a sense, but they really didn’t understand the politics of it as deeply as we did.

When I got back from Vietnam I was very, very militant. But because I believed, and still do, that the pen is mightier than the sword and because I didn’t want to just end up as a frontpage lurid headline and break my mother’s heart, writing helped turn me from that violence.

Archived Material

No posts

Podcasts

No posts