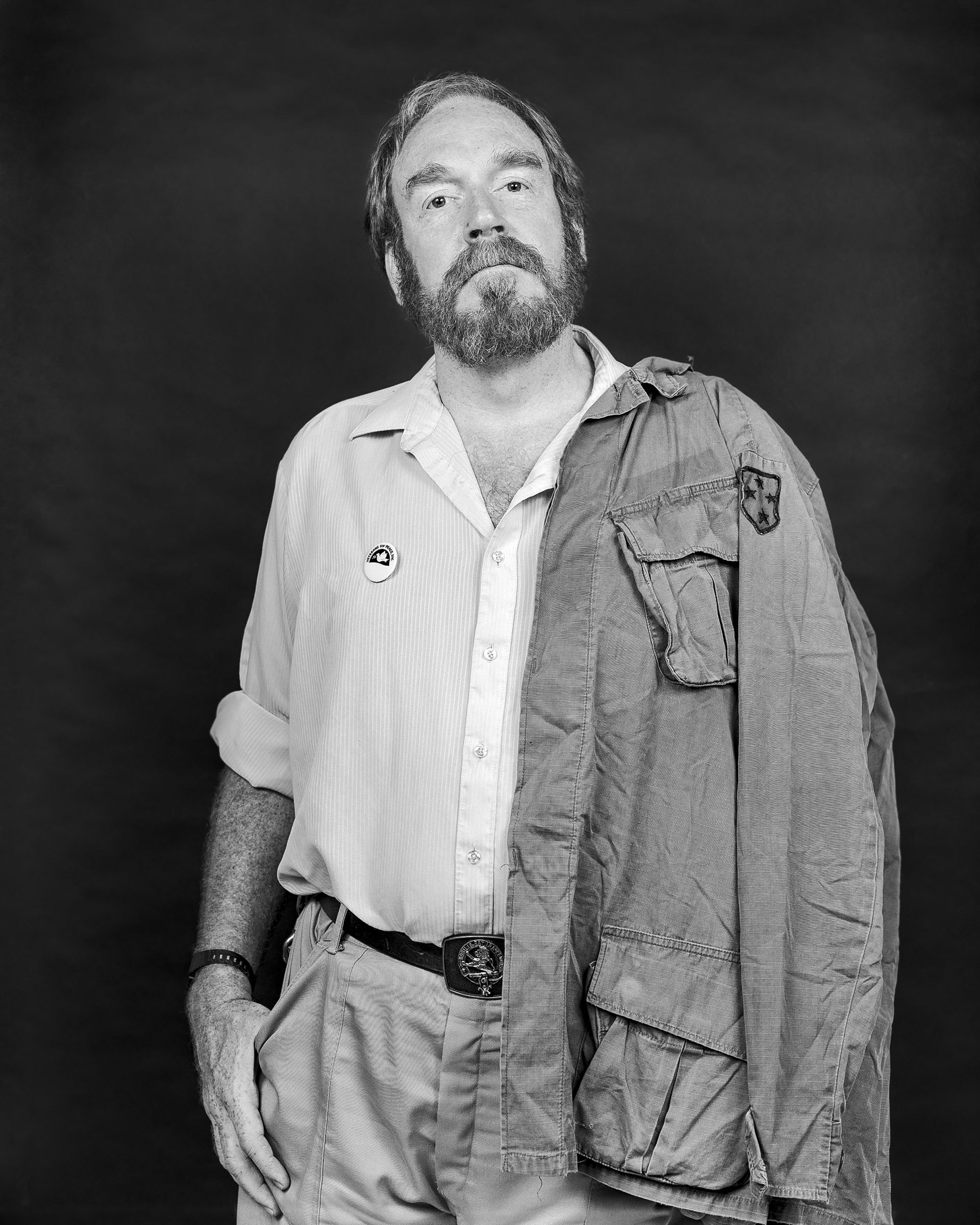

At my first duty station in Vietnam, a Military Intelligence detachment, I refused to work with South Vietnamese interpreters who were using physical coercion in order to extract “the truth” from North Vietnamese and Viet Cong soldiers. There were four or five ARVN interpreters who were working with the Military Intelligence unit. And although I was language-trained in Vietnamese, it was standard operational procedure to have a Vietnamese interpreter with Americans in order to make sure no nuances of the language escaped any one and maybe to check up on us.

The first person I was to interrogate was an NVA soldier who had been brought in during Operation Iron Mountain. I started doing basic debriefing of the individual and realized that the Vietnamese interpreter was pulling and twisting on the man’s ear lobe and had it stretched down somewhere below his chin line. I told him to stop, and he did, only to start again after a few moments. I stopped the questioning and requested another Vietnamese interpreter and the same thing happened. I decided to end the debriefing session.

My next interrogation was of a suspected Viet Cong who had been shot. He was from a small village on the Laotian border. We had nothing that showed he had ever been a Viet Cong and I classified him as being civilian, possibly civilian defendant. The South Vietnamese I was working with to debrief the fellow, kept pinching off his IV (intravenous) tubes while we were talking. I told him several times to stop, but it was totally out of my control. I tried using three other Vietnamese interpreters after that and they also abused the prisoner; either cutting off his IV or pulling and twisting on his ear lobe or twisting a handful of flesh from his side in order to create pain. I refused to work with them. As a result, I was transferred out of the MI detachment.

I was later asked to interpret at the evacuation of a refugee camp and was sent in unarmed to an area with several South Vietnamese from the Province Recon Unit. I felt something was wrong … very, very wrong. I was told we were looking for a woman and some children who were supposed to be on the farthest edge of the village. We got to village edge and they told me it was just a little farther. We went through the tree line, and still farther. I realized they were acting very nervous and suspicious. They ran forward to a small ravine and I started running back. When I got to the edge of the village I heard gunfire behind me. The fire was directed at me; they were not supposed to bring me back alive. Earlier I had reported the use of a “birdcage” (a cage constructed of barbed wire wrapped around a captive and then hung in a tree) in a Vietnamese compound and they were forced to take it down. Shortly after this incident my hooch was fragged with a percussion grenade.

I was threatened with court‑martial several times, but I always thought about what would my parents have done. What would be the right thing to do, not from the Army’s point of view, but from my family’s and my community’s. I consciously thought about that and came to the conclusion there were things I had been raised not to do and couldn’t and wouldn’t do.

Archived Material

No posts

Podcasts

No posts