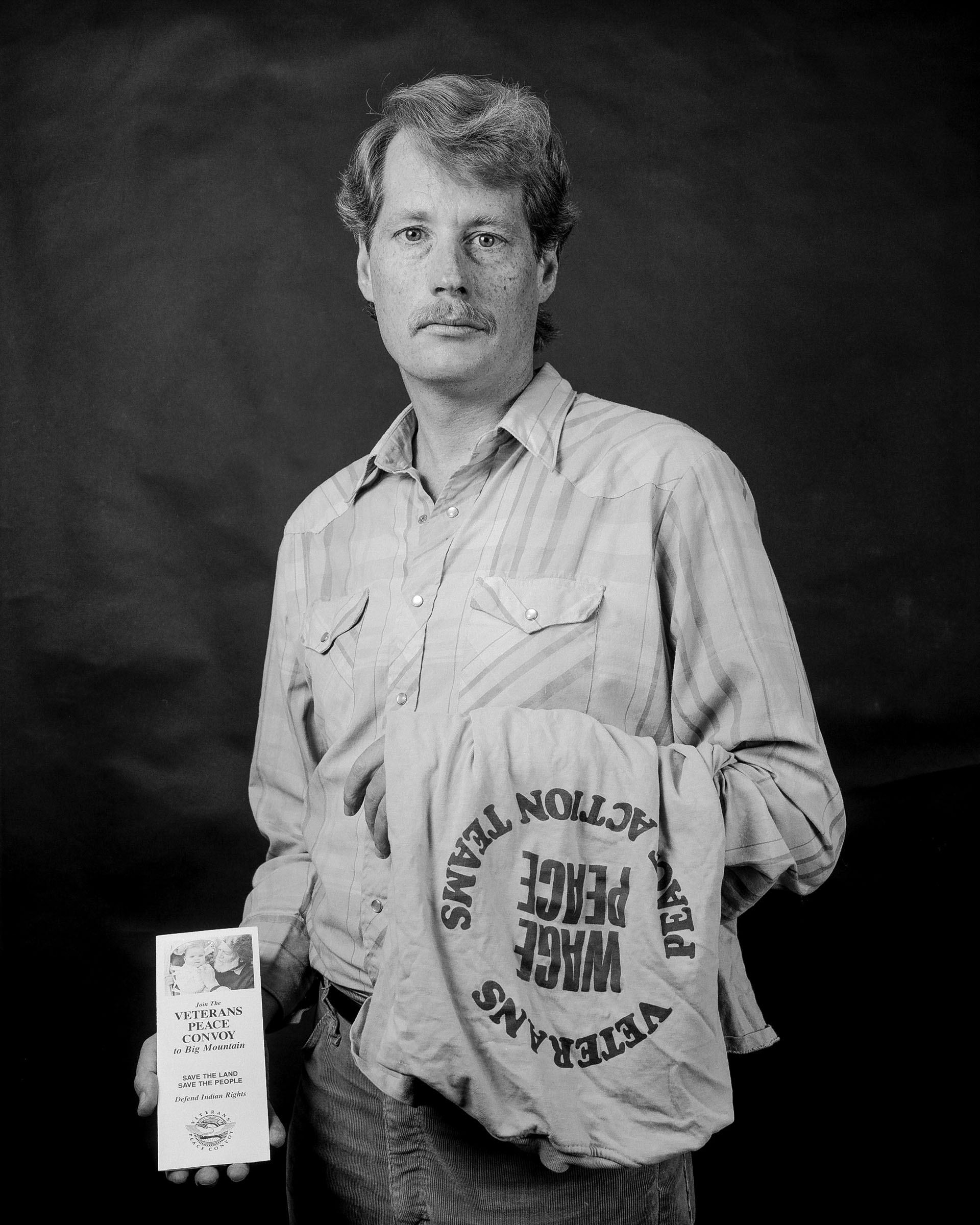

Basic training was really brutal and rude. It kind of shocked me and the inhumanity of it reinforced my doubts about war. Just to survive the day-to-day routine, I suppressed my anti-war feelings for a period of several months. The training reality is so intense around you that it doesn’t leave room for much else. I got an ulcer when I was going through Special Forces medical training. I sat down with myself and said, I think you know what this ulcer’s about. I had, in a sense, become a little schizophrenic. I told myself, you’re going to have to decide who you are and who you’re going to be. So I fenagled a leave back to the San Francisco Bay area. I sat down in the backyard of my home and wrote this long, dramatic letter to the papers and had my picture in both papers. The Chroniclesaid, “Anti-war Green Beret Drops Out.” I went back to Fort Bragg to face the music. I went through about six months of pretrial legal maneuverings, and realized they were going to make an example of me. Eventually they convicted me of two counts of refusing orders to go to Vietnam, and sentenced me to ten years in prison. But I wasn’t present at my court-martial. I had already deserted — I decided my freedom was more important than I thought.

I got a passport sent to me in Canada, which was really a godsend. After a couple of months I decided to go to Europe. I lived in Germany for six months and I was totally broke, so I called home. My mom told me the FBI had been there the day before and for the first time they got her goat, which is great because my father was a cop and she’s used to cooperating with the system. The first couple of times they had Navy Intelligence visit her and she said, “Oh, they were such nice young men.” But this time they called her a liar because they couldn’t get the information from her they wanted, because she didn’t have it. So I just happened to call the next day and she says, “They know where you are, they’re getting closer.” I’d been postponing doing the obvious thing of going to Sweden. I arrived in Sweden in November of ’69, the day of the first snowfall there.

If you arrived at the wrong port and got into the wrong hands in Sweden you could have some troubles, because despite being a very progressive country, it’s still got right-wing, fascist elements. There’s cops in Sweden that wear American flags on their shoulders, even at that time, and they supported Nixon and the war. But Stockholm was pretty well set up. There were U.S. social workers that were on the government payroll to help out. And there was the American Deserters’ Committee, which had gained a lot of political allies and was on top of things. So when we arrived we were basically accepted with open arms, and given a stipend to buy a good winter coat, for rent, and language training.

The majority of the guys there were deserters rather than draft resisters. Most of them, frankly, were not strongly motivated by anti-war idealism, although certainly anti-war attitudes were part of the total context that we were in.

On the other hand, a significant minority of us were extremely active — that’s where I became politically active and aware. We did a lot of good work, in conjunction with the Swedish anti-war movement. Of course, you have to keep in mind that during the entire war, no more than 800 men came to Sweden, and there were never more than 500 at one time at the height, and they were spread around Sweden, as opposed to Canada, in which there were at least 60,000 men who came up there fleeing the war.

Archived Material

No posts

Podcasts

No posts