In training they gave you basically two things: either you were going over there to help the people of South Vietnam fight against Communist aggression, or you were going over to kill commies. My background made me definitely be against the idea of going over to kill commies, so I sort of latched onto the idea we were there to help people — I wanted to believe we were doing the right thing. When I got to Vietnam it really didn’t take me but about one day in-country to realize it wasn’t true. As soon as you get there the first thing they tell you is you can’t trust any of them, they’re gooks, they’re not human beings.

On January 20, 1967 we were overrun by NVA and this guy ran off to my hole and started shooting in and I started shooting out and he shot me through the knee and I shot him through the chest and killed him. I laid in the hole all night. When the battle ended in the morning, they pulled me out of the hole, put me on a stretcher and carried me over to this guy I’d shot. He was sitting there dead leaning over against this old tree stump, just sitting there, with his rifle across his lap and a couple of bullet holes through his chest. The sergeant said, “Here’s this gook you shot, you did a good job.” I looked at the guy; he was about the same age as me and I didn’t feel any pride in it at all. They gave me a bronze star for that. This is the only person I can say with any certainty that I shot and it blew my mind.

While I was in the hospital in Japan I found a book which was called The New Legions by Donald Duncan. Duncan had served 18 months in ‘Nam training ARVNs, and he resigned from the military and basically wrote we’re fighting on the wrong side. When I read that book it made a lot of sense to me because that’s what I saw. So I made a decision I was going to come back to the United States and start working against the war.

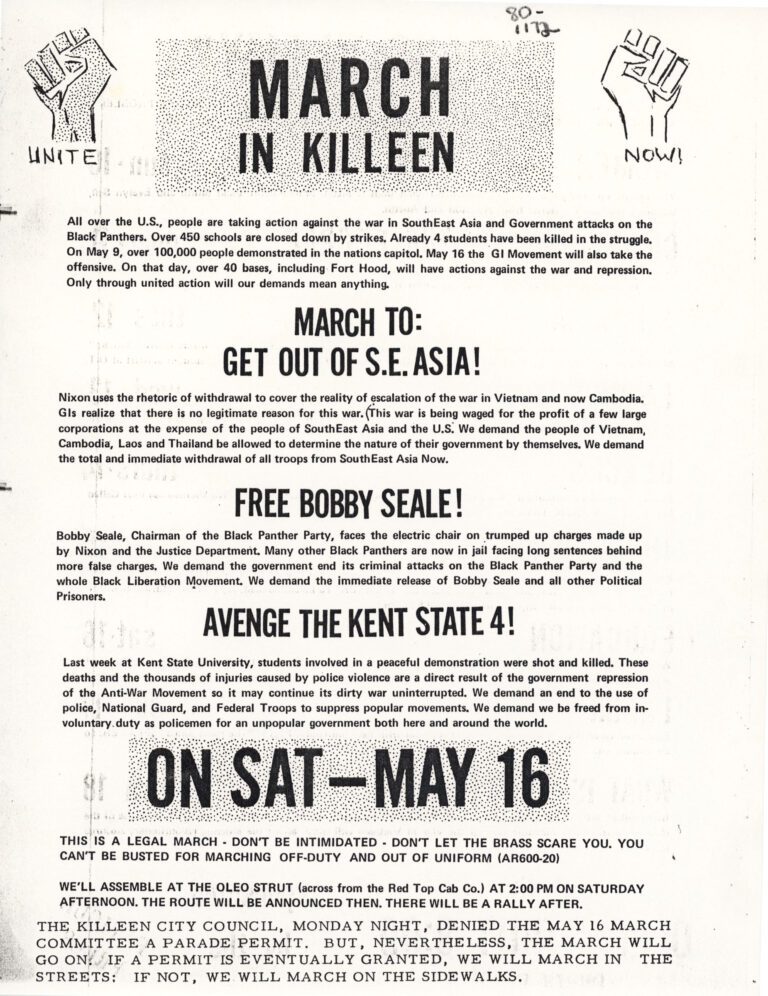

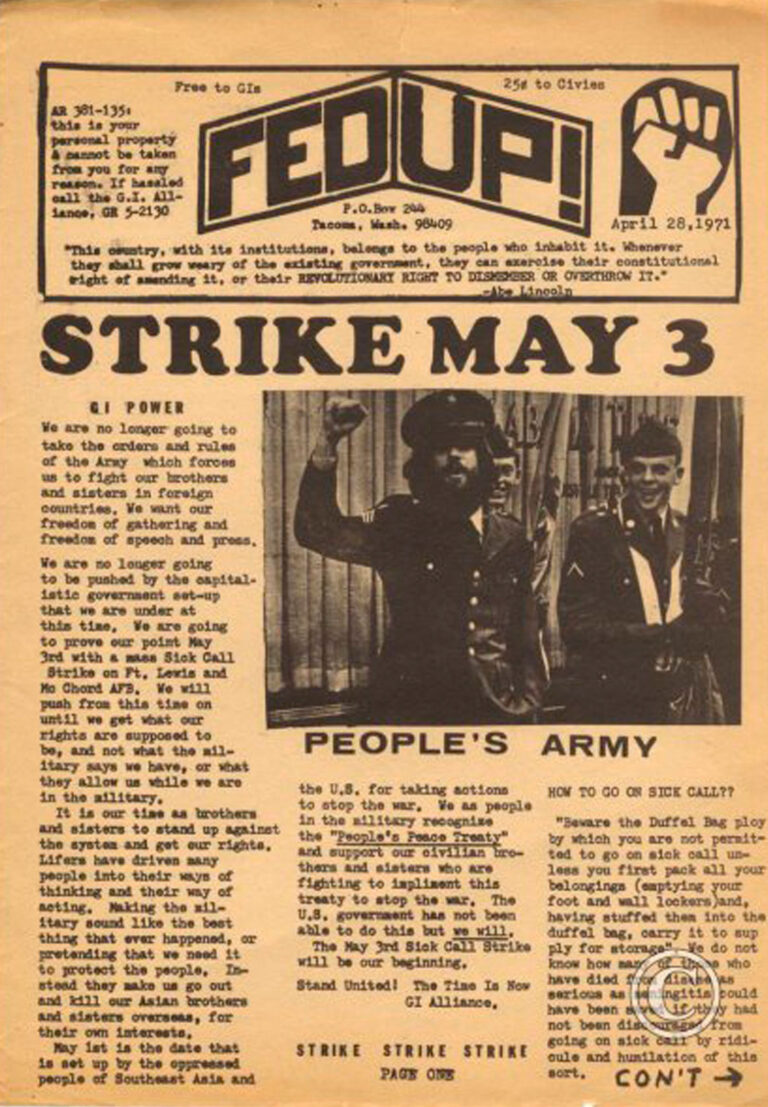

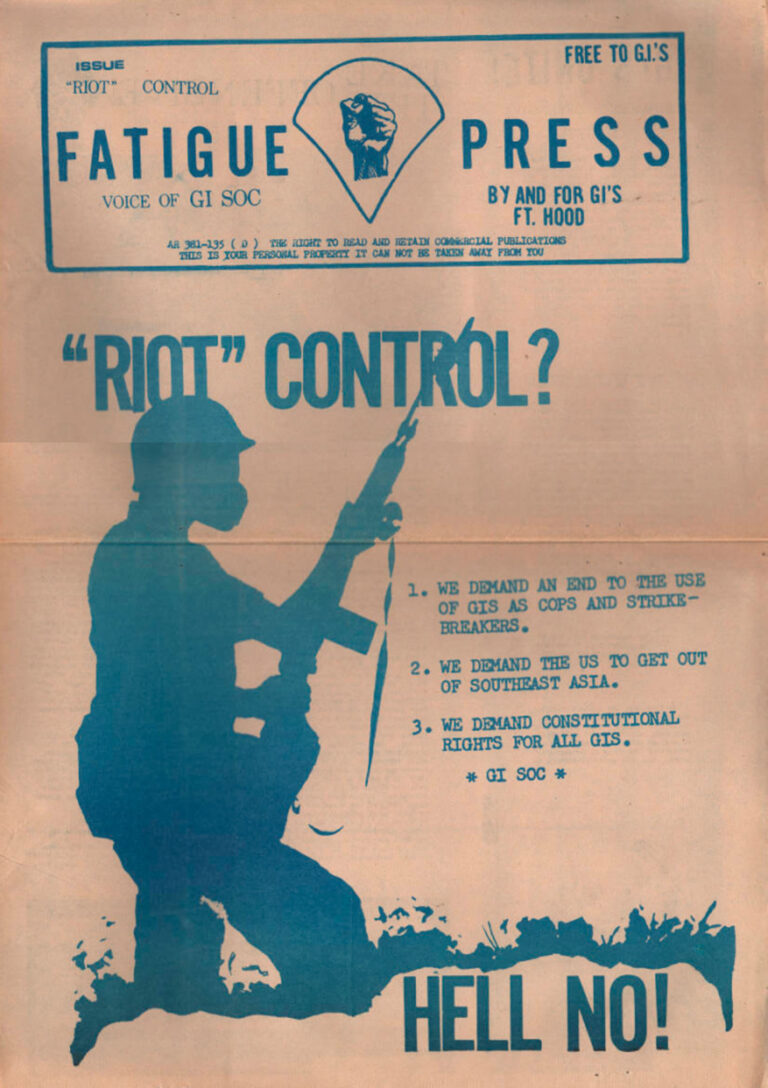

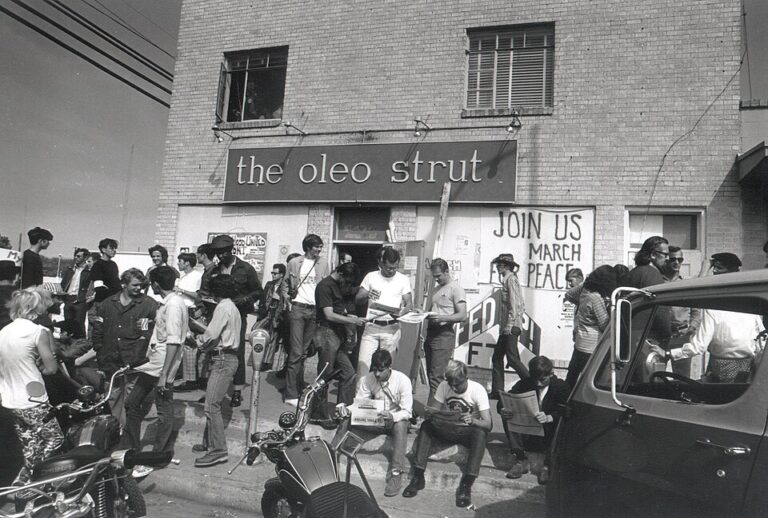

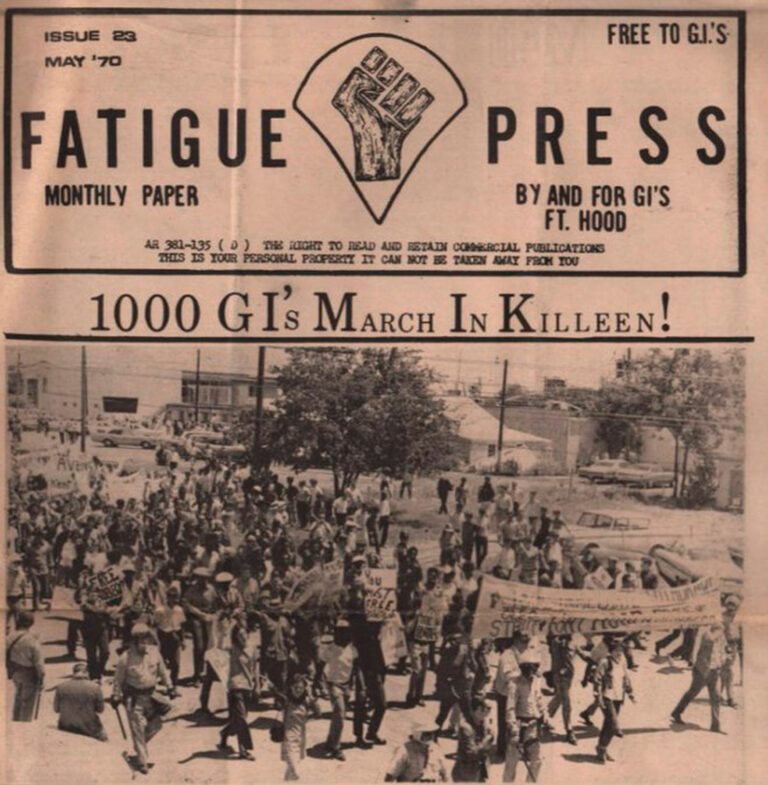

I was sent down to Fort Hood and that’s when I really got hooked up with the GI movement. They had a coffeehouse in town called the “Oleo Strut,” and a newspaper called the Fatigue Press, which I got involved with. The Democratic Convention was scheduled for that summer, ’68, so they began having riot control training. They called it “The Garden Plot.” We decided to organize a movement against it because there was a lot of opposition to the idea of going to Chicago. A lot of guys had just come back from ‘Nam and they said, we fought the Vietnamese, now they want you to fight Americans. A lot of people identified with the demonstrators on different levels.

We put together a meeting on the base. We met on a big ballfield right in the middle of the base and there must have been about 70 or 80 GIs there; black guys, white guys. We got a sticker mass-produced, a black hand and a peace sign. The plan was we were going to distribute them to all the troops that were opposed to being used. If they put us on the streets against the demonstrators, we were going to put these stickers on our helmets as a visible sign of solidarity with the demonstrators in opposition to what we were doing. About three days after that almost everyone that was at the meeting got taken off The Garden Plot roster for being subversive. They told the troops if anyone was caught with a sticker they would be court-martialed.

Archived Material

Podcasts

No posts