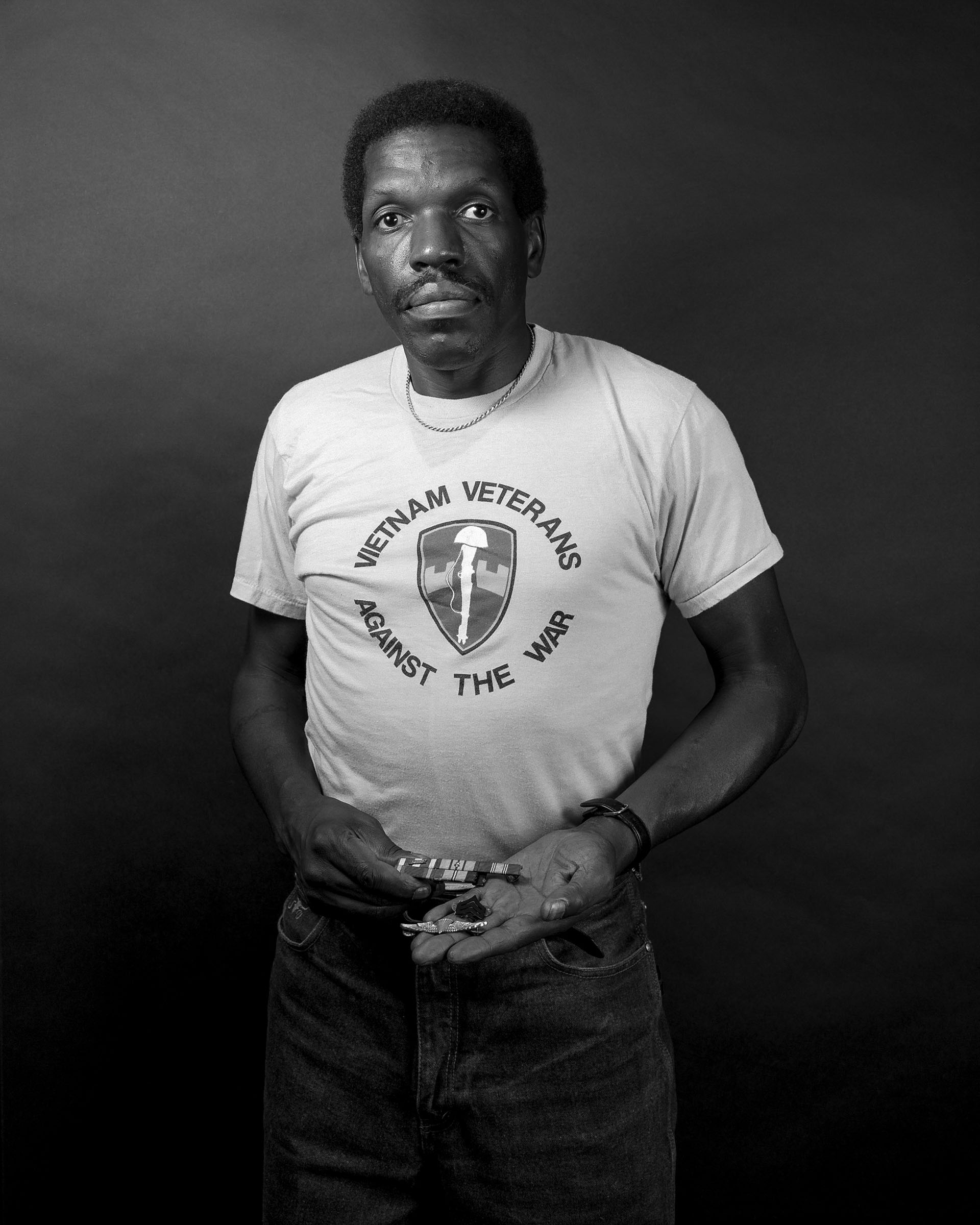

My father was in the military in World War II, and even though he was in a segregated army, it was very much a part of his life experience. Being a veteran wasn’t something that was looked down on; it was one of the few things Black men had that they could hold up as being honorable, as being accepted, as being proof that you had just as much right to anything that was going to be given out, even though you didn’t get it all the time. That’s why a lot of the hostility and resentment came, because they didn’t get their just due. But they did get some things out of it. My father went to mechanics school on the GI bill. The house my mother lives in right now was bought on the GI bill. We probably would not have been able to do it without the GI bill. My father talked about his personal experiences in the war all the time. I could tell you where he was stationed because he told us a thousand times. He made us sit down and listen to the stories, but he didn’t really elaborate on the negatives and the racism.

For me and other Black GIs in Vietnam in 1967, things were changing. Things going on in the States affected our behavior there. Some of the same Black consciousness, the whole Black power movement, was taking place there too. We were growing Afros, expressing ourselves through ritualistic handshakes, Black power handshakes, African beads, hanging around in cliques, trying to eat up as much of the Black music as we could get our hands on. We kind of segregated ourselves; we didn’t want to integrate into what we considered the white man’s war. For the first time I was looking at the enemy, not so much as the enemy, but as another minority, brown people. The North Vietnamese reminded us of it too.

People started really trying to educate themselves about how the war started, where the war was going. We read a lot of the books, Confessions of Nat Turner, Soul on Ice, all of the Black publications, Ebony, Jet, as much as we could see because we wanted to be a part of it. There were some nights we had 20, 30, 50 brothers hanging out. When we went into a mess hall, we ate together in certain parts of the mess hall. They were trying to make us get haircuts, cut those Afros off, and people were going to jail to keep their hair. We tried to spend almost all of our time together, the “Bloods” in Vietnam, we tried to have all Black hooches. The brass would try to prevent this, they would try to assign us to integrated hooches and stuff like that.

When I was put in the brig, it was like another awareness. Because the brig was like, there were white Marines in the brig, but the overwhelming majority were Black, much like the jails were back in The World. It just made you more bitter, more conscious, more hard, more militant, gave you more of a reason for being what you were and to resist and to fight, and make sure you educated yourself and educated others.

You laid down at night and there was just so much tension going through you, with all the racial stuff, the war itself and we were so young. That year in Vietnam was like 20 years, you saw so much and witnessed so much.

Archived Material

No posts

Podcasts

No posts