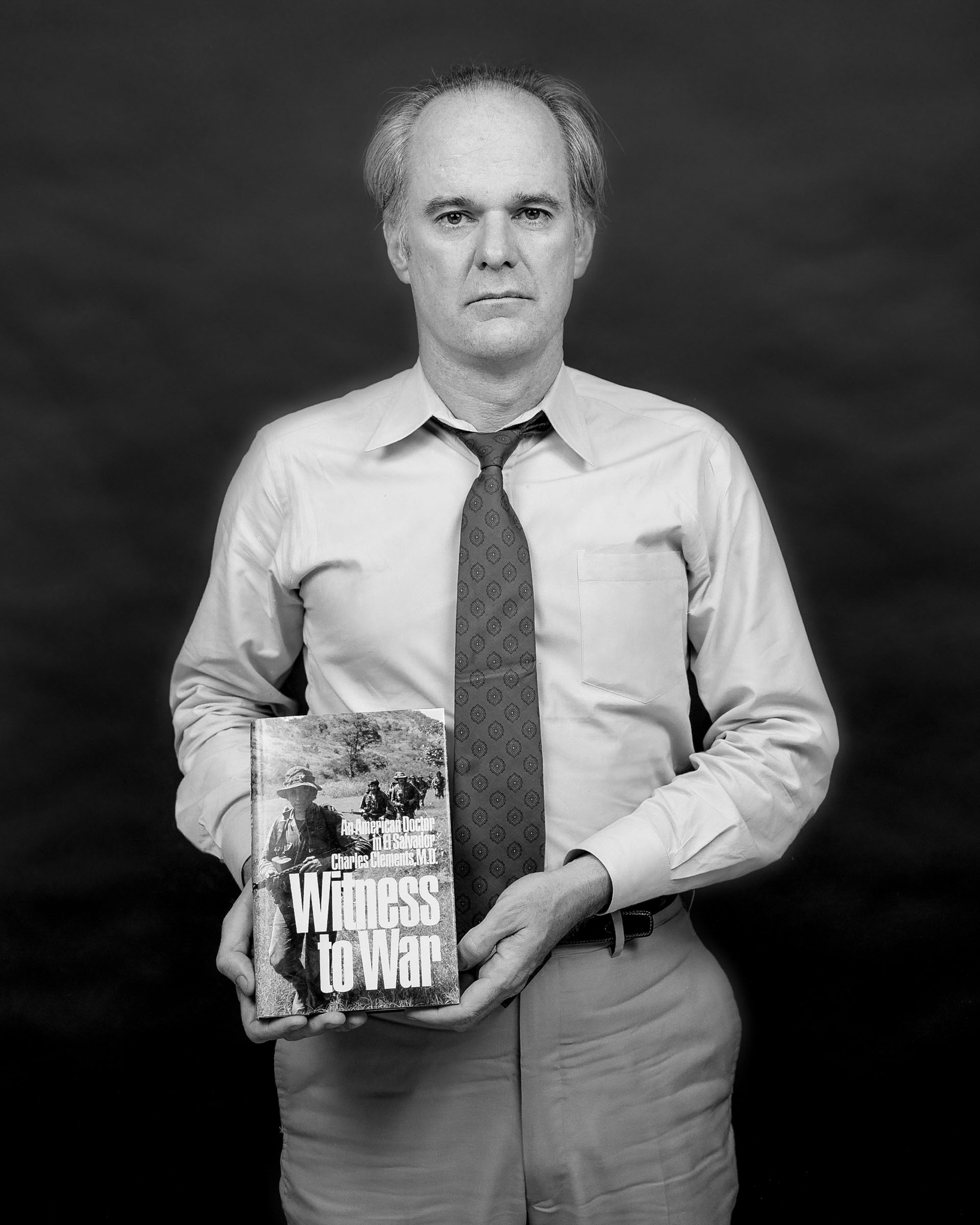

I grew up on military bases because my father was in the Air Force, and I suppose I was groomed from the time I was a little boy to go into the Air Force. My brother went to the Air Force Academy and I followed. At the Academy we were instilled with a tremendous sense of duty and discipline, and of honor and ethics; a theme that one dealt with almost everyday there because one could take a pencil from somebody else and if you didn’t return it, that was considered an honor violation and you would have to turn yourself in and leave the Academy. It was a black and white world. I think it was that sense of honor that probably lead me to my refusal to fly anymore in Vietnam.

I entered pilot training with the clear understanding that I didn’t want to kill anybody, but I can’t tell you why I felt that way. I trained in a C-130, then went to Vietnam and slowly began to see things differently. I began to have a real revulsion about what was going on, but I never thought about quitting.

I flew a secret mission to Cambodia and I remember looking out of the plane and seeing vast areas that looked like the moon. Only one thing did that: B-52’s. I realized we were conducting massive bombing operations there. We began ferrying troops from Saigon to Parrot’s Beak, positioning troops for an invasion. I was furious. I had a cold so I declared myself unfit to fly.

I went off to California for a few days and went to an anti-war rally at San Francisco State with a friend. I felt, this is it, I’m not going to go back, I’m not going to fly any more missions. Somehow the organizers got me to speak and I just told people, “I’m a lieutenant in the Air Force and I’m not going to fly any more. I’ve seen a lot of terrible things and I’m saying no.”

I went back to Vietnam and asked for a transfer to a unit that didn’t have anything to do with Vietnam. Some months later I got a call to go to San Antonio where I saw this Air Force psychiatrist. He said, “Don’t worry Clements, we’ll have you back in Saigon in a week, you’re in the old three-year slump.” I said, “You’re pretty fucked up if you think I’m going back.” I talked about the Phoenix program, about secret bases in Laos, about flying plane loads of money down there for this black marketing scam, about secret missions into Cambodia, and coups and invasions and I think he thought I was totally whacked.

He gave me an envelope and sent me across town to some place. I went across town, gave them this envelope and they gave me a pair of pajamas. I had gone in the back door of a psychiatric ward and there I was! I couldn’t make any telephone calls, I couldn’t have any visitors, and I was given medications. If I didn’t take the medication I was told I would be strapped down and injected. I didn’t know if I was crazy or not, but I was beginning to think so because the nurses and doctors were intelligent, educated people, and they were treating me like I was one of the other patients. Then the major from across town came and said that if I would agree to go back to Saigon they would drop all this psychiatric stuff. That was a turning point for me because I knew if I was crazy, I was crazy because I chose to be. Soon after, a friend of mine kind of broke into the ward. We were supposed to have dinner the night I had disappeared and he finally found me.

Archived Material

No posts

Podcasts

No posts