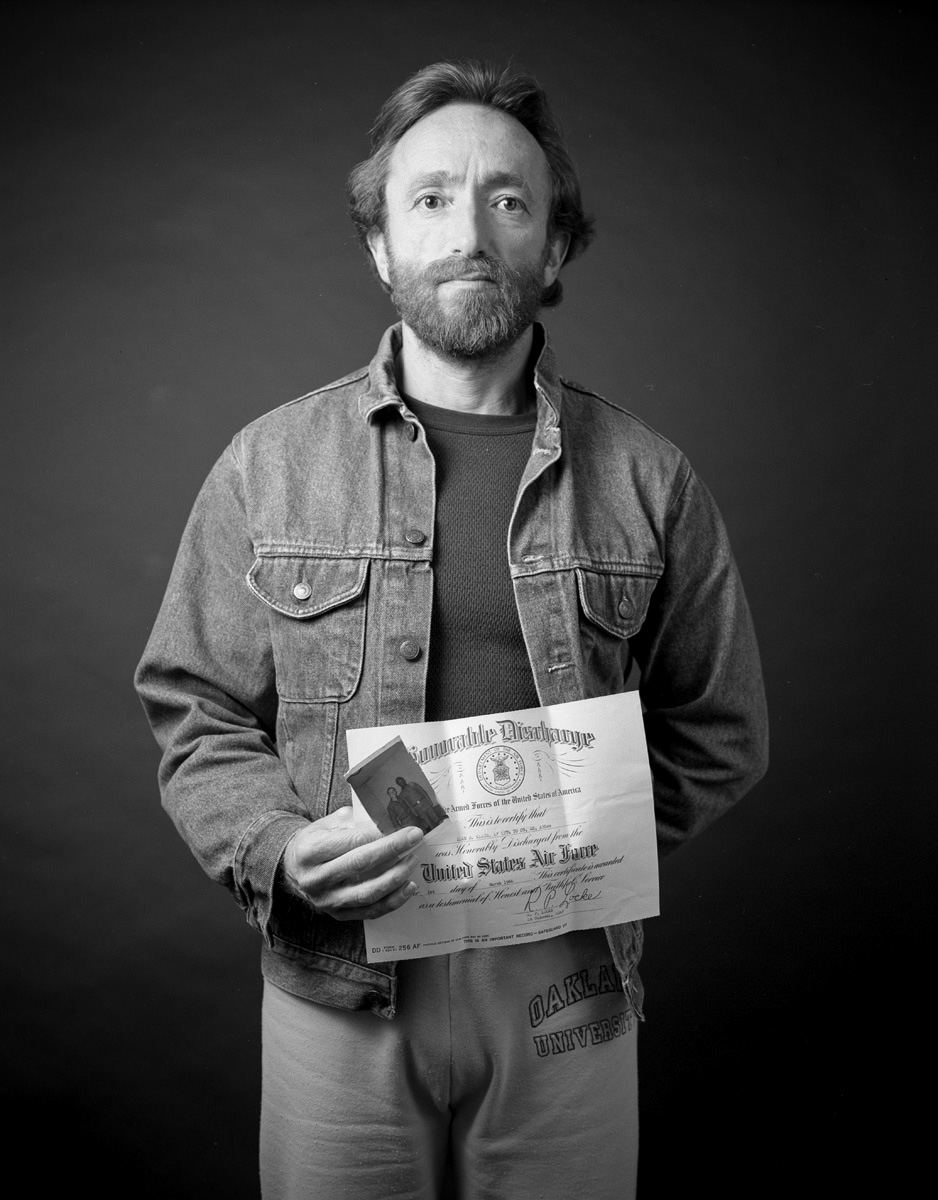

I was born in Germany in 1946 to parents who were survivors of the camps. All my relatives were victims of World War II. The ideas I had about war were maybe different than what an average American kid had because I grew up thinking it was my lot to go into the camps, just as it might have been the lot of a normal kid to go into the military. I remember being real small, my eyes were tabletop level, and I would watch my father and his friends playing cards, and all of them had the numbers tattooed on their arms. They would deal cards and tell stories about how they survived. And that’s what I thought I would do.

The very same day I got my draft notice I went to the Air Force recruiter and enlisted. On one of my trips home I was in O’Hare Airport waiting on military stand-by. This guy comes by and he’s got his hand right on the counter, this doughy, pudgy hand, all pinkish. I glanced up his sleeve and saw that patch: Airborne. And then I looked up at his face. He had been burned and he was all puffy. And it was only when we started talking that I realized he was black. It was in his voice; he was from Yazoo, Mississippi. I was just dumbstruck. What got me most was that he was 17 and I couldn’t tell his age and I couldn’t tell his color. He had been denuded of that. I went home depressed about that. My father met me and he was telling me about a big killing he made on the stock market with a munitions company. Suddenly it became crystal clear. It was a bolt of lightning. I said, he’s the one who should have been in that young guy’s place — he has a real reason to fight, he needs the war to make money. Those are the guys that ought to be fighting this war, not that kid. And certainly not me.

From that point on, it was never the same again. I came back and announced to my friends, from here on in I’m opposed to the war and I’m going to fuck up this place as bad as I can. I’m not going to Vietnam, but I’m not going to be sitting around doing nothing either. We decided what we could best do is destroy the efficiency of our outfit.

Everything we touched was no longer assumed to be used to further the efficiency of the U.S. military. Everything we did was designed to be messed up, sabotaged, or basically deemed done by incompetents, and thereby they would exert more energy to keep us in line and less to wage war. So little by little, it might be a truck that was neglected, it might be the tip of a wing that was damaged, just anything to keep it off-balance.

Finally, in the fall of ’66 a group of us decided we would go AWOL. We got back and turned ourselves over to our officer and he said, “If you promise not to leave, we will just confine you to barracks.” The other guys said, “Absolutely.” I said, “Fuck you, not only do I promise not to leave, I’m gonna leave right now.” That was the end of it, I was in jail.

Just before I was released I heard the reason I was being let out was because we got this directive that said, all the people who committed the following offenses would hereby be dismissed and at present rank. So it dawned on me, and somebody else told us, there were thousands and thousands of guys who were doing time, costing the military a lot of money. It’s really interesting in retrospect to think that, unbeknownst to me, I was part of something larger. I was operating in a vacuum, but I wasn’t alone. Rather than feeling anonymous, I found tremendous solace in knowing there were so many other people who were as ill-formed as I, groping along trying to find their way, and reacting to anger and fear, but all of us, in our own way coming to the same point.

Archived Material

No posts

Podcasts

No posts