On April 30, 1975 North Vietnamese Army tanks crashed through the gates of the Presidential Palace in Saigon, officially bringing to an end the twelve-year war against the United States and unifying North and South Viet Nam into one country. The “American War,” as the Vietnamese call it, was sandwiched between the battle for independence against French colonists and border wars with Cambodia and China. The Vietnamese have been fighting wars of independence for centuries. The war with the United States was distinguished by the level of firepower used by American forces and by the fact that it was also a civil war; brother against brother, anti-communist against communist, families divided.

The portraits and interviews presented in this exhibition are among 90 collected during three trips to Viet Nam; in 1993, 1994 and 1996. We found people to interview through our research, through friends in Viet Nam and the U.S., or from the associations with which we worked. The National Photographic Association and the Foreign Press Center coordinated our visits, because, at that time, the Vietnamese government required that any cultural work be sponsored by official organizations. Working within the bureaucratic and political restrictions of an authoritarian government, the difficulties of interviewing through a translator, and confusions over cultural differences often led to frustrations. But the warmth of the people we interviewed, and the compelling power of their stories, made the obstacles important to overcome.

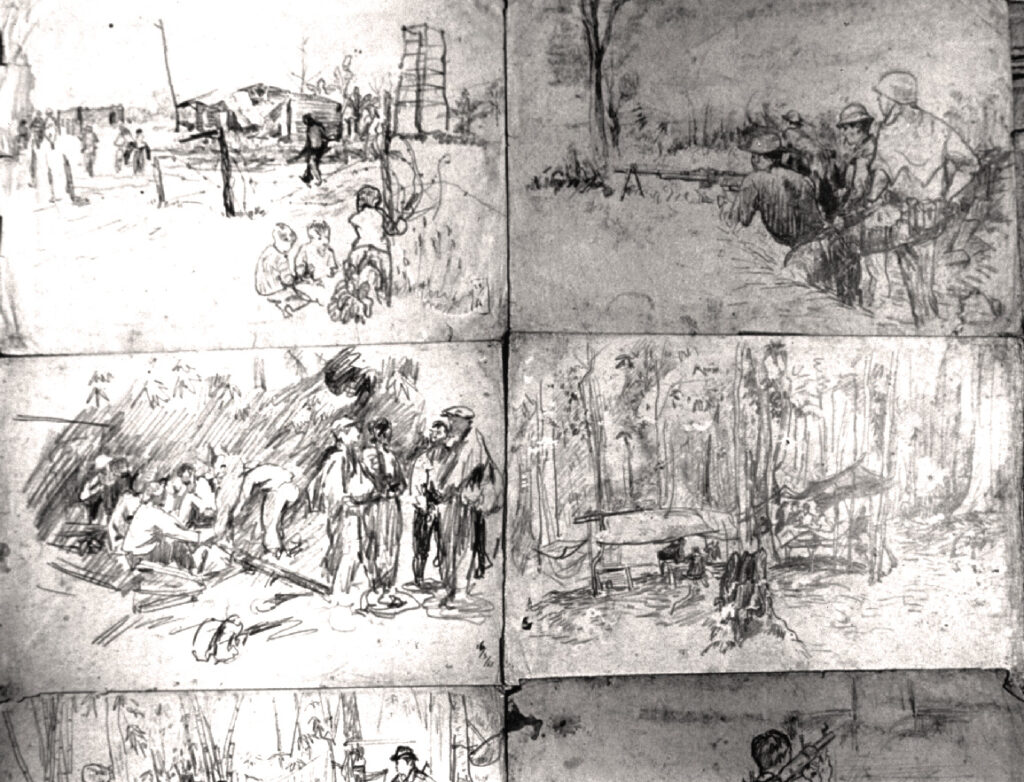

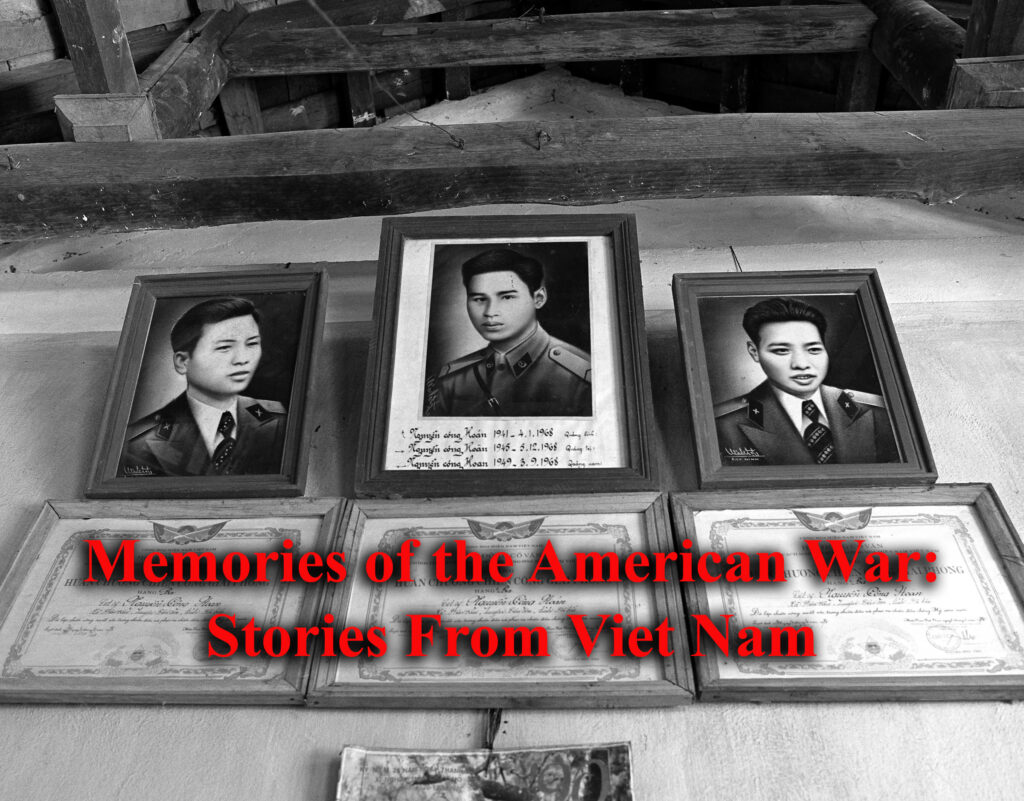

We were welcomed into people’s homes with infinite kindness. Even the poorest of people shared their tea, fruit and sweets with us. Oftentimes we were the first Westerners they had ever met. On numerous occasions, particularly in small villages, we would conduct the interview with a crowd of twenty or thirty people looking on. Initially we were the curiosity, but we began to realize that many of the villagers listening in had never heard the stories related by their family members or neighbors. People willingly shared their painful memories, lifted a shirt or pant leg to show us a wound, or in some cases gave us old photographs they had ripped out of their scrapbooks.

For American and Vietnamese youth born after 1975, the conflict is a distant history. The long years of war and severe poverty have given way to foreign investment and tourism. As this younger generation looks to the future, we hope Memories of the American War will preserve an important part of the past for the people of both countries.