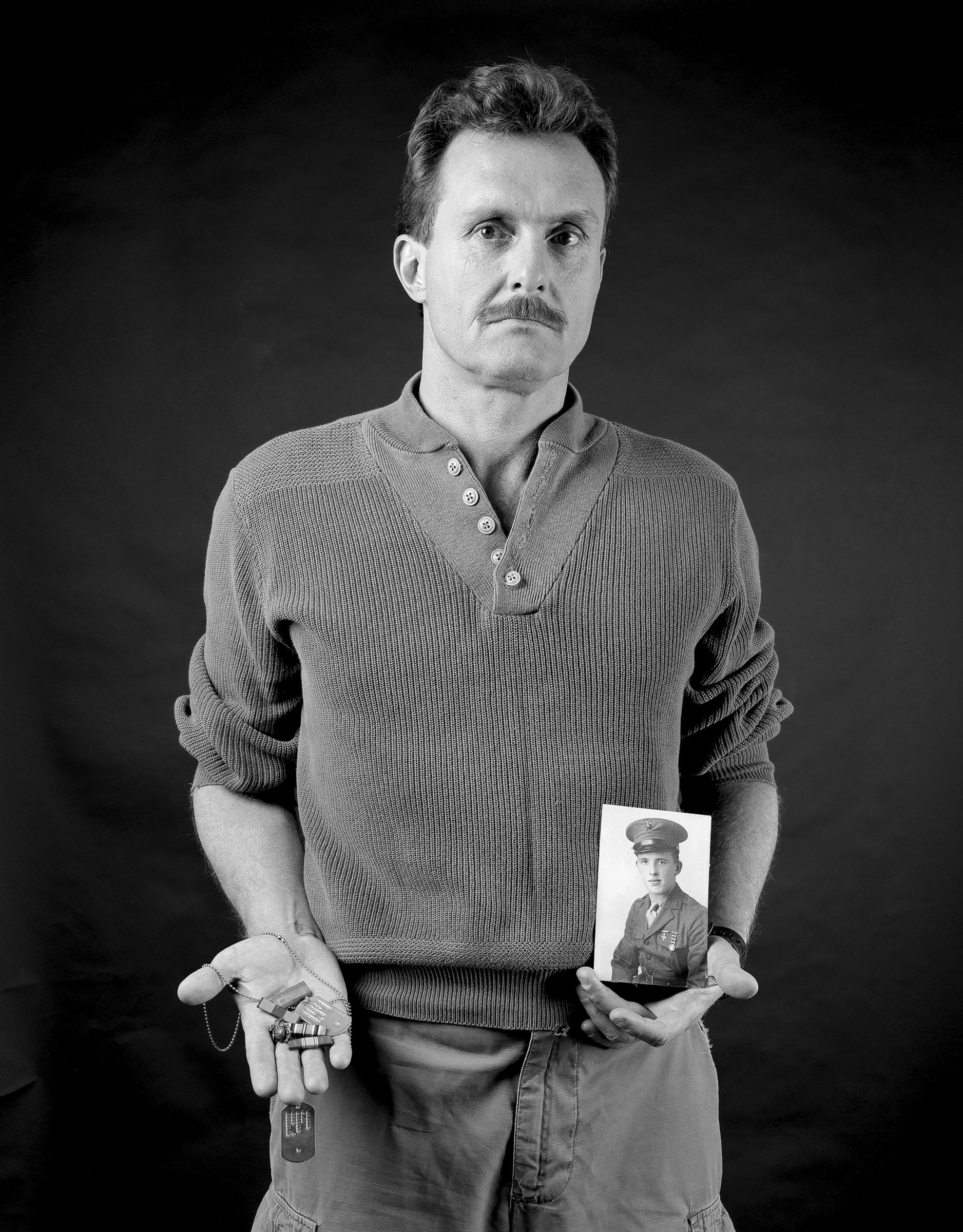

I was born immediately after the Second World War. I always think I was born in the shadow of the bomb, and there was never a time in my childhood when I thought that men didn’t go to war. My father was a perfect example of a modern day warrior, and I thought he never looked better than he did when he was in his uniform. Once I knew my father had been in the Marine Corps, I always knew that I would go in the Marine Corps someday.When I was a kid my father kept these medals and ribbons and other Marine Corps paraphernalia in a little cigar box that he had tucked away in the back corner of his dresser. My brothers and I used to visit that little cigar box as though it were a shrine, in which these magic talismans were. I never tired of going there and opening the cover, tingling with anticipation, looking once again. I guess I saw them as badges of courage and of honor, and there was never a time in my childhood that I doubted whether I would myself wear these emblems and earn these badges.

When I was a kid my father kept these medals and ribbons and other Marine Corps paraphernalia in a little cigar box that he had tucked away in the back corner of his dresser. My brothers and I used to visit that little cigar box as though it were a shrine, in which these magic talismans were. I never tired of going there and opening the cover, tingling with anticipation, looking once again. I guess I saw them as badges of courage and of honor, and there was never a time in my childhood that I doubted whether I would myself wear these emblems and earn these badges.

After I refused to go to Vietnam, I wanted only to get rid of them, to forget about them, forget what they had once meant to me. I was angry at the time because, at least in that period of my life, I felt that every symbol I once valued as a symbol ofsomething good and decent, was now in my mind a symbol of its opposite. And I think I wanted to be rid of the ties that still bound me to my father; I have to say that I wanted to be rid of his disapproval.

It’s only been in the last five years or so that I’ve been able to pick these things up. You know, it’s funny that I even have some of them. I threw virtually everything I had away, but there were some things I kept. But I never looked at them until five years ago. I began going to that little corner of my own life, one by one pulling out some things; I guess a kind of talisman again. To pick, for instance, this globe and anchor; to pick that up was like picking up something radioactive. I didn’t know what it meant to me. I knew that it still meant something deep, but I was afraid of it because, even now looking at it, I get that old sense of patriotism. There’s nothing wrong with love of country, but I get afraid of where that feeling leads; into a mindless, unquestioning, uncritical acceptance of policy by governmental leaders that got us involved in Vietnam in the first place.

Without exception, the people I knew who had gone to Vietnam felt they were doing something honorable. But many people would say to me it was the most fucked up thing they have ever done in their lives and wish they could get it out of their sleep, their nightmares. And in that sense, I felt I had made the right decision. I knew from listening to them that I would have been — if I survived at all — a complete basket case. I also felt convinced that my analysis of the war was correct; that it was not a self-serving one to justify my own behavior, but it was real. A more fucked up war couldn’t be imagined. And it was clear to me that the Vietnam veteran was being scapegoated for the war, that collectively the United States had called upon vets to go and do something and then had turned its back on them afterwards.

Archived Material

No posts

Podcasts

No posts