I was born and raised in San Francisco, in the Polk District, which at that time was mostly a Chinese district. The Chinese have a real different slant on war. They see it as one of the miseries of life that comes around periodically, like famines, and it was never glamorized. In Chinese society the hierarchy was nobles at the top, scholars directly under them, farmers, then merchants and last of all soldiers.

I got my draft notice in 1968. I didn’t know what to do. I was no longer convinced the war was right, but I wasn’t totally convinced it was wrong either. I finally decided I would volunteer in order to get into the medics. One time we were in the line for the mess hall, a real long line. We could see people whispering to each other and passing it down. And when the whisper got to me, the guy in front of me said, “They’re killing women and children in Vietnam.” I said, “Who’s killing women and children? The Viet Cong?” And he said, “No, we are.” When we got to the front we saw this newspaper rack with pictures of My Lai on the front pages. I can’t describe what that did to us. There could no longer be any doubt as to who’s right and who’s wrong.

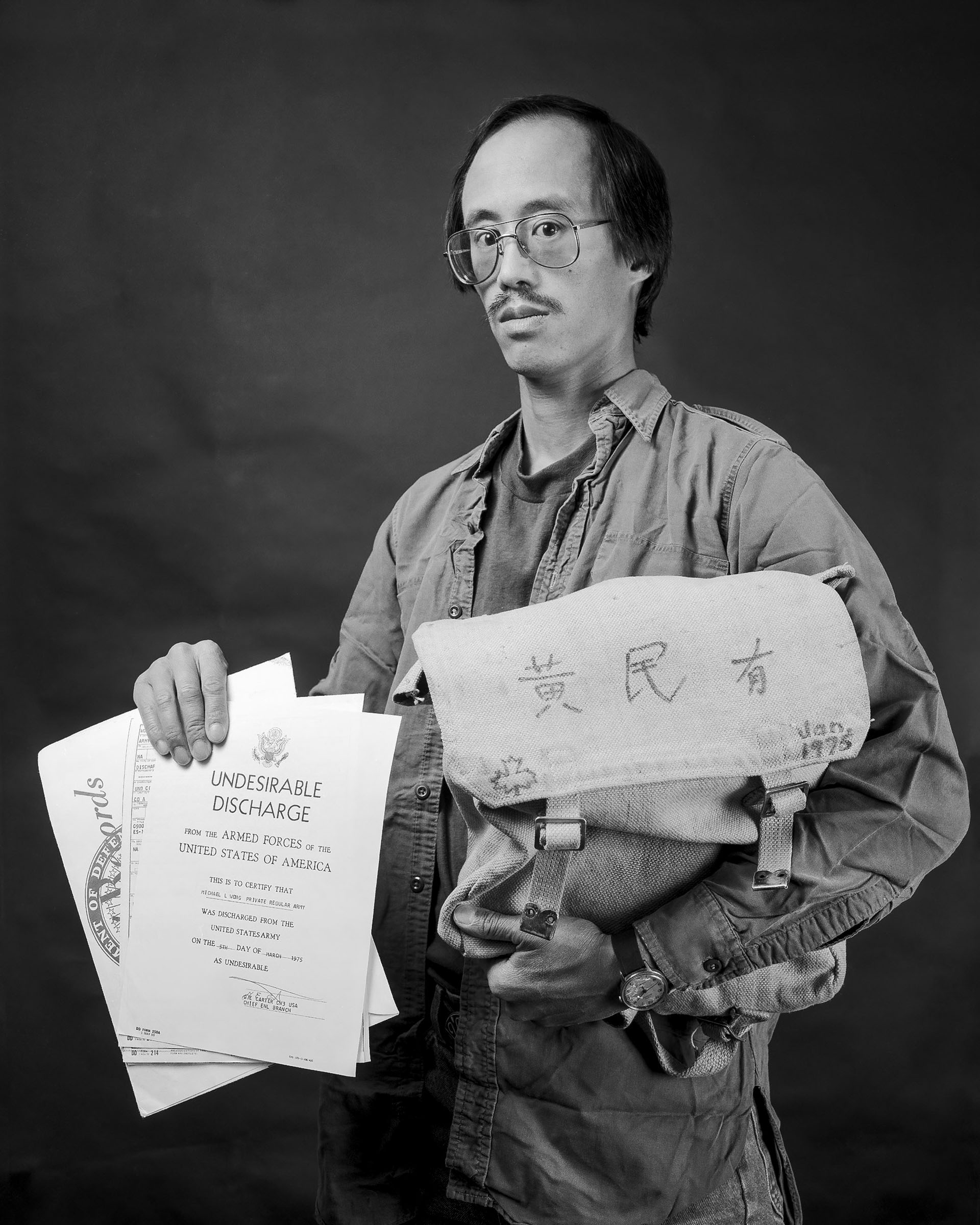

I received orders for Vietnam and decided to go AWOL and then turn myself into the Presidio Stockade, plead guilty to AWOL and then they’d have to throw me in the stockade. That would become my permanent duty station and I could apply for CO. They had me in the stockade for like 20 minutes and a guard comes and pulls me back in the office. This lieutenant wants me to sign this thing saying they’re releasing me from the stockade and putting me back on Vietnam orders, and I was to proceed immediately to Oakland Army Terminal for shipment to Vietnam. My lawyer says, just sign it. So they released me and my lawyer took me back to his office and said, “They were going to stick a gun in your face and put handcuffs on you and then put you on the plane. I managed to talk them into releasing you into my custody. My legal responsibility is to take you to Oakland Army Terminal. If you resist, of course, you’re a trained soldier, I can’t very well stop you.” I was so young and naive, I had no idea what to do. I finally got the hint and I split.

I knew Canada was my only remaining option. But to go to Canada was to desert, to run away, to say I’m a coward. I was just going around and around in circles. So I went to this Chinese movie theater to stop thinking about it. What was showing was a movie about Chinese guerrillas fighting the Japanese during World War II. I came out and realized I only had two choices: either I could go to Vietnam and do to the Vietnamese what the Japanese had done to the Chinese in World War II, or I could go to Canada. The question had been framed in black and white: do you want to be a murderer or do you want to be a coward? And I finally decided that the worst thing that can happen with a coward is he hurts himself, but a murderer not only hurts himself, he hurts other people too. And so I went to Canada.

People think we make these decisions lightly and that all the people that went to Canada just ran away. I was prepared to go to prison and fight my case for as long as the war lasted. Going to Canada was the hardest decision of my life. It was questions of manhood, giving up your family, your country, your friends, giving up everything you knew. I went to Canada with the assumption I would be there for the rest of my life, that I would be an exile, a criminal, wanted by the FBI … and that I could never come home again.

Archived Material

No posts

Podcasts

No posts